Waltzes (Strictly No Dancing)

I’d like to start this programme in an unusual way: with no real introduction by me and a piece of non-classical music. Here we go…

That was Jacques Brel, a Belgian, singing La Valse a mille temps, a hundred count waltz. As the music gets faster, he sings that it is way less danceable but still charming.

And that’s the subject of this programme: waltzes that were not necessarily written to be danced to.

I wrote this programme just before New Year, a time that’s long been associated with waltz music. But in this programme you won’t hear a note of the kind of music played annually at the Musikverein in Vienna – and you certainly won’t hear anything from the Strauss dynasty – Johann I and II, Joseph and Eduard, the people who made the Viennese waltz so very popular.

But you will hear some waltz music by composers you wouldn’t readily associate with the waltz. However, that’s not really the case with Sibelius.

That was the Waltz, one of five pieces for violin and piano, Opus 81, by Jean Sibelius, written in 1917. Sibelius’s first instrument was the piano but he did learn to play the violin. It’s a charming set of miniatures composed very much for the salon rather than the ballroom. Sibelius loved the waltz; it was his favourite dance and he used it in around 100 compositions. I think you will agree that what you heard there was reminiscent of Tchaikovsky’s ballets.

Speaking of ballets, Prokofiev completed the music for Cinderella in 1944 and the ballet was premiered at the Bolshoi the following year. After its premiere, Prokofiev compiled his Waltz Suite, drawing upon waltzes previously written for the stage or the screen: the opera War and Peace; the Soviet film Lermontov and the ballet Cinderella. And it’s from Cinderella that the next piece comes. This is Happiness, from Prokofiev’s Waltz Suite.

Let’s stay in Russia now. I mentioned the Soviet film, Lermontov, a few minutes ago. Well, Prokofiev wasn’t the only big-name Russian composer to write film music. Shostakovich could write achingly beautiful music. He could also write music that’s stark and harrowing. And he could, and did, effortlessly churn out stuff for films that I think is so banal that it wouldn’t be out of place in a fairground. Listen to his waltz for the film Sophia Perovskaya, a 1967 Soviet film about a revolutionary who was executed for taking part in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II.

Let’s continue with this Russian theme for a while. From the moment the waltz became popular in the ballroom composers began writing waltz music for the piano, and next comes a set of three piano waltzes by Russian composers, beginning with this, by Alexander Scriabin.

That was Scriabin’s Quasi Waltz. “All music must be communicable in dance”, he once said. I wonder how true that is of the next piece, by Stravinsky.

That was the waltz from A Soldier’s Tale, Stravinsky’s theatre work “to be read, played and danced” which was premiered in 1918.

Now, a very brief but somewhat more conventional piano piece

That was the Farewell Waltz, written by Mikhail Glinka in 1831.

Now comes a waltz that you could probably imagine dancing to. I couldn’t – I can’t dance to save myself. This is Dvorak’s Waltz in A Major, Opus 54, No. 1. Dvorak originally wrote that as a piano piece for two hands but in 1880 arranged it for string orchestra. And very amiable it is too.

Doing a programme about waltzes that weren’t necessarily written to be danced to isn’t as daft as it may at first seem. There are hundreds of pieces I could have used: piano pieces by Brahms, Chopin, Grieg and countless others, for example.

I said earlier that this programme wouldn’t feature any music by Strauss. Well, I meant it but next comes music by Strauss – though not one of the Strauss family famous for waltzes. Richard Strauss, no relation, wrote waltz sequences for his opera Der Rosenkavalier. The opera was premiered in 1911 and Strauss came in for some stick for his anachronistic use of the waltz, but then, he seemed to make a point of writing music that didn’t belong to his age. So, let’s hear something from Der Rosenkavalier.

I’ve assured you that there’ll be no music by the Strauss dynasty in this programme. Well, next comes music that was written as a tribute to Johann Strauss II, The Waltz King. Erich Korngold, who was born in Vienna, wrote Straussiana in 1951. It was his last orchestral work and it’s a curious pot pourri of melodies from some of Strauss’s lesser-known waltzes.

If you like waltzes I think you will find this quite charming; it’s certainly a well-orchestrated work, despite or because of the fact that it was written for American school orchestras. Let’s hear it.

That piece, Straussiana, was pretty conventional stuff, wasn’t it? The sort of music that might have tempted you to put on a ballgown and glide round your living room floor, especially if you are a woman.

I came to a curious conclusion when I was researching this programme. I thought it would be appropriate to include a symphony that features waltz music but there are remarkably few of them. Mahler included hints of the waltz in a couple of his symphonies, and I’m sure there were other composers who did likewise though I can’t think of them offhand.

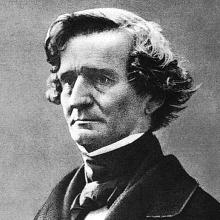

So that leaves me with two clear candidates: the third movement of Tchaikovsky’s 5th Symphony and _Symphonie fantastique _by Berlioz. I chose the latter because most folk will be familiar with Tchaikovsky’s waltzes, written for ballet.

Berlioz wrote Symphonie fantastique in 1830. I’ve told the story of this work before so I’ll precise it thus: it’s a musical story of an artist’s self-destructive passion for a beautiful woman. The symphony is in five movements, each one with a name: Passions, A Ball, Scene in the Fields, March to the Scaffold and Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath.

Needless to say, the waltz is in the second movement, A Ball. Two harps lead the waltz as the music alternates between the dancers and spying on the artist as he tries to get the attention of his beloved. It’s easy to picture the artist in the swirl of a grand party, with colourful sights and sounds all around him, yet all he can think of is this young woman. Let’s hear it now.

Earlier, I featured some piano waltzes and I thought I would finish this one with another one: a minute-long piece by the Czech composer Bohuslav Martinu. He wrote three editions of short piano pieces called Puppets between 1912 and 1925. This is from the second book and it’s called the Sentimental Puppet’s Waltz.

Now we come to what I and always planned to be the main item in this programme, and I think this is the first time I have featured music in a programme that I have previously featured.

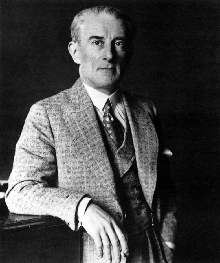

However, I felt I could not leave out Ravel’s La Valse, not least because it’s music that utterly captivates me. It is, like so much of Ravel’s output, a wonderfully-crafted, imaginative work of genius.

Here’s the story. Ravel was a big fan of the waltz. He liked the dance’s “wonderful rhythms” and in 1906 he wrote of his plans to write a piece in tribute to the waltz and to Johann Strauss II. His idea was to call the piece ‘Vienna’. As it happened, Ravel didn’t return to his idea until 1919, prompted by a commission from Sergei Diaghilev.

Ravel worked on three versions of La Valse simultaneously: one for a large symphony orchestra, one for piano solo, which was probably intended as a rehearsal aid, and a version for two pianos. The latter was the one in which La Valse was first performed for Diaghelev. But he rejected La Valse, saying it was only a “portrait of a ballet”, not a real ballet. He was right, I think, but his reaction put an end to the relationship between the two. When the two men met again several years later Ravel refused to shake Diaghelev’s hand, and Diaghelev challenged Ravel to a duel – which never took place. That was their last encounter.

Ravel conceived La Valse as a visual work and even wrote a detailed programme for its first part. It read:

Through whirling clouds, waltzing couples may be faintly distinguished. The clouds gradually scatter: one sees […] an immense hall peopled with a whirling crowd. The scene is gradually illuminated. The light of the chandeliers bursts forth […]. Set in an imperial court, about 1855.

La Valse opens softly as if to create the impression of a mist, and various bits of melodies slowly appear. The waltz goes through various mood changes: from elegant to pompous; slightly melancholic, and so on. But towards the end it all goes downhill and the waltz’s character becomes almost hysteric. The music explodes into a violent climax almost as if the waltz itself is destroyed. At least, that’s how La Valse is generally interpreted.

But there’s another interpretation. When Ravel wrote La Valse, World War I had just ended, and Vienna was no longer a city of glory. According to one review, La Valse as a symbol for “the birth, decay and destruction of a musical genre through a new, nightmare-ish musical language. Ravel saw the waltz as a symbol of old Europe with all its beauty, dignity, and civility. But in time something got lost and it all began to descend into ugliness, instability and chaos.

Here then is La Valse.

I had intended to finish this programme at this point but maybe it would be churlish not to include in it one of Chopin’s many waltzes. This is from Chopin’s 3 Waltzes, Op. 64, No. 1 in D-Flat Major and it is played by Arthur Rubenstein.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Waltzes (Strictly No Dancing) playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.