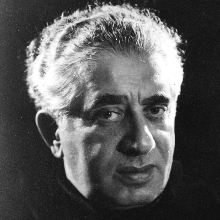

Aram Khachaturian

The composer Aram Ilich Khachaturian, 1903-1978, was the greatest Soviet composer: discuss. Well, I don’t want to put anyone on the spot, so I’ll discuss.

He was the greatest Soviet composer because he was the only great composer who lived in the Soviet Union who was a supporter of the Soviet regime. Prokofiev and Shostakovich may rank above Khachaturian as composers but they were not communists. They were largely apolitical and each found his own way to live with the regime. Khachaturian, however, was an avowed communist and embraced the regime whole-heartedly. He was a Hero of Socialist Labour, he was awarded the Order of Lenin three times, he was People’s Artist of the Soviet Union, he received the Order of the October Revolution … I could go on.

But what’s all this got to do with his music? Quite a bit, I think.

Khachaturian was born in Tbilisi, capital of Georgia. His parents were born in the present-day Azerbaijan but they and their son (actually, they had five children), considered themselves to be Armenian. Tbilisi was the administrative hub of the entire Caucasus region, and was a multi-cultural city. Khachaturian grew up listening to music from Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan.

In 1922 both Georgia and Armenia became part of the Soviet Union. Khachaturian later wrote:

The October Revolution fundamentally changed my whole life and, if I have really grown into a serious artist, then I am indebted only to the people and the Soviet Government. To this people is dedicated my entire conscious life, as is all my creative work.

Like Stalin, Khachaturian wasn’t Russian – he was proudly Armenian, and though he didn’t actually join the Communist Party until 1943, he was an enthusiastic supporter of the Soviet Union of which his homeland was part. That meant he would allow his music to be influenced by many of the non-Russian elements of the Soviet Union. Music from all the Soviet republics as important to him.

The USSR exercised firm political control over its diverse regions, but it also followed a policy of encouraging arts that had their source in the culture of the people, wherever they may be in this vast empire. Khachaturian championed that cause.

There’s no doubt this has impacted on his reputation in the West. Nevertheless, he is known for some great music which is much played and loved all over the world.

Khachaturian's style was melodious, with strong rhythms and colourful orchestration. He was inspired by the folk music of Armenia and neighbouring regions, and his works were’ a continuation of the 19th‐century nationalism of the Russian “mighty five”: Balakirev, Cui, Mussorgsky, Borodin and Rimsky-Korsakov.

It’s time for some music. This is something of a well-crafted curiosity by Khachaturian. It’s played by the Armenian Philharmonic Orchestra.

I played that piece not for any musical reason but to underline Khachaturian’s commitment to the Communist cause in the Soviet Union. It was the Communist Party-pleasing Ode in the Memory of Vladimir Ilych Lenin, written in 1948.

Much of Khachaturian’s reputation is built around the music he wrote for ballet, and you are now going to hear three pieces from one such ballet.

Gayaney was first staged at the height of the Great Patriotic War, in December 1942, in Perm, near the Ural Mountains, where the Kirov Ballet had been evacuated. Khachaturian was awarded the Stalin Prize for it. The action takes place on a collective farm in Armenia in the early days of the war. Gayaney, a cotton-picker, is married to the disreputable Giko, a drunkard and a coward. She denounces him, but he sets fire to bales of cotton and takes their child hostage. Gayaney is injured by her husband but saved from his further threats by the arrival of the Red Army Border Patrol and its heroic leader. Giko is sent to jail, leaving Gayane free to marry the leader of the Border Patrol, with whom she has fallen in love. Their marriage gives an opportunity for celebratory dances from Armenia, Georgia and the Ukraine.

Let’s start, then, with a familiar tune, the famous Kurdish Sabre Dance.

Now, more from Gayaney. This is the Dance of the Young Maidens, and like the first piece is played by the Bolshoi Symphony Orchestra under Alexander Lazarev.

As a youngster, Khachaturian thought about a career in engineering or medicine. However, when he was 18 he went to Moscow to join his brother Suren, who was stage director at the Moscow Art Theatre. The following year he enrolled at a music school, simultaneously also studying Biology. Initially he studied cello but then took lessons in composition, and he soon began composing. In 1929, he enrolled at the Moscow Conservatory to study composition and orchestration. He married a fellow student while there.

I’ve decided not to play today’s music in chronological order and so next comes the slow movement from Khachaturian’s Piano Concerto.

Khachaturian wrote this piece in 1936 and it was premiered in strange circumstances in Moscow the following year. It seems there was only an upright piano available for the premiere, which was held in an open-air venue. During the performance the wind blew off the conductor’s glasses and, being unable to read the score, he had to continue conducting from memory.

The concerto is one of only a few pieces that uses something called a flexitime, which is a cross between a musical saw and a glockenspiel, if you can imagine such a thing. It appears in this, the second movement.

The Piano Concerto was an overnight sensation and established Khachaturian’s reputation in the West.

In 1935, Khachaturian wrote his First Symphony, music which was very much inspired by his Armenian roots and which celebrated the 15th anniversary of the foundation of the Soviet Armenian Republic.

The years preceding and following World War II were very productive for Khachaturian. In 1939 he made a six-month trip to his native Armenia "to make a thorough study of Armenian musical folklore and to collect folk-song and dance tunes" for his first ballet, Happiness, which he completed in the same year.

In 1942, at the height of the Second World War, he reworked it into the ballet Gayaney. That work was a great success and it earned Khachaturian a Soviet State Prize. Khachaturian returned the money of the prize to the state with a request to use it for building a tank for the Red Army.

Both Gayaney and Khachaturian’s Second Symphony, which he wrote in 1943, were warmly praised by Shostakovich, a composer with which Khachaturian was later to share a particular distinction. Until Stalin, very few people who rose above the parapet politically, artistically or even professionally, escaped the wrath of the State at some time or another. In 1947, despite being an ardent communist, Khachaturian, along with Shostakovich, Prokofiev and some others, was denounced under what was known as the Zhdanov Decree. It was determined that their music was too advanced or difficult for the masses to enjoy. The works of all three composers were considered to “smell strongly of the spirit of modern bourgeois culture, the complete denial of musical art.”

Like Prokofiev and Shostakovich, Khachaturian hastened to confess his musical guilt, declaring that he recognised his own errors and was grateful to have them pointed out. His humble apology soon got him back in the State’s good books. He was given an apartment in Moscow building where Shostakovich and Rostropovich lived, and the Armenian Government gave him an estate with servants and chauffeur-driven cars. “I suppose that makes me a capitalist,” he once said.

Honestly, I doubt if there was much in Khachaturian’s work that the state could take exception to. Khachaturian was by nature a generous and optimistic man, and his music reflected that. It had a certain cheerfulness – even the tragic movements in his ballets tend to be picturesque rather than moving.

There’s a theory that what really turned the Soviet hierarchy against Khachaturian for a brief spell was the fact that he tended to wear double-breasted suits, which were regarded as American and therefore capitalist.

Next up is the third movement of Khachaturian’s Violin Concerto. He wrote three concerti, one for piano, which you heard a bit of, one for cello and this one. It’s a violin concerto but it was subsequently arranged, with Khachaturian’s permission, for flute – and very striking that version is too.

The Violin Concerto, which was composed and premiered in 1940. He worked on the concerto in the tranquillity of a composers retreat west of Moscow; he said of the composition that he "worked without effort ... themes came to me in such abundance that I had a hard time putting them in order”.

This movement, Allegro vivace, has been called "a whirlwind of motion and virtuosity”. I think it’s one most ebullient concerto finales ever written, and it’s one that could have been composed for Perlman.

In 1941, a year after the last piece you heard was written, Khachaturian composed incidental music for a play called Masquerade by the Romantic poet and playwright Mikhail Lermontov and set in 1830s St Petersburg aristocratic society. The play premiered in a Moscow theatre in June 1941. It was the last show staged by the theatre before the Germans invaded, and thanks to Hitler the play’s run was cut short. Lermontov, by the way, is a name that came from the name Learmonth – the playwright’s paternal family could trace their roots to a Scottish army officer, George Learmonth, who settled in Russia in the 17th century.

There’s a story that having written his Violin Concerto Khachaturian felt he was on something of a roll and so when he was asked to write music for Masquerade he took on the challenge immediately. However, he soon regretted his decision as the theme for a central waltz in the production eluded him. There is a section of the plot where the play’s principal character, Nina, says, ‘How beautiful the new waltz is!’ she goes on to describe a work somewhere between sorrow and joy. That line put the composer under pressure and caused him sleepless nights. However, with a little help from a friend, he came up his theme.

Three years after writing the music for the production, he worked it into a symphonic suite of five movements, a waltz, a nocturne, a mazurka, a romance and a galop.

You are going to hear the Moscow Symphony Orchestra under Veronika Dudarova play all five movements. The Waltz, the first bit, is one of his best-known works.

In 1950, Khachaturian started conducting and teaching composition. During his career as a university professor he continued to champion the folk music of the Soviet republics.

Also in that year, he began work on his third and final ballet. I’ve saved Spartacus till last because, well, it was his last internationally-acclaimed work.

You know the story. Kirk Douglas, sorry Spartacus, leads a slave uprising against the Romans. Khachaturian completed Spartacus in 1954 and was promptly awarded the Lenin Prize for it. Quite apart from the quality of the music, the story of Spartacus played well with the Soviet regime, although the story in the ballet takes considerable liberties with the actual story of Spartacus.

The ballet was premiered in 1956 and was at first deemed a qualified success. Now, it’s one of Khachaturian’s best-known works and is performed the world over.

Before the ballet’s first showing, Khachaturian arranged the music for it into four orchestral suites, and you are going to hear excerpts from those suites, all of them played by the Royal National Scottish Orchestra conducted by Neeme Jarvi.

First, this is the Introduction to the first suite, featuring the Dance of the Nymphs.

Now, this is from Suite No. 3: Dance of a Greek Slave.

Now, more music from the third suite. This is Variations of Aegina and Bacchanalia.

Now, our last piece, and it’s one of the most played pieces of classical music. The Adagio of Spartacus and Phyrigia will forever be associated with the very hammy 70s TV series The Onedin Line, but of course it has nothing to do with the sea and ships.

In the ballet, Spartacus is a Thracian king who is captured by the Romans with his wife Phyrigia. Spartacus is forced to entertain the Roman consul, Crassus, by fighting and killing his friend in the gladiatorial ring. Later, Spartacus and his friends rebel and rescue Phyrigia and other captured slave women. Aegina, concubine to Crassus, insists that the slave army is pursued immediately. But before that can happen, Spartacus and Phyrigia celebrate their escape, to the tune of this adagio...

As anyone who has seen the film will be able to tell you, Spartacus was eventually defeated by Crassus, and put to death by crucifixion, together with his followers. To Karl Marx Spartacus was the first great proletarian hero, a champion of the people, while the ultimate fate of Crassus, killed in 53BC during the course of a campaign that had taken him to Armenia, doubtless had a particular significance for Khachaturian.

Following the success of Spartacus towards the end of the 1950s, Khachaturian’s remaining years were devoted less to composition, and more to conducting, teaching, bureaucracy – ie, supporting Soviet causes – and travel. Khachaturian died in Moscow on 1st May 1978, after a long illness, just short of his 75th birthday.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Aram Khachaturian playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.