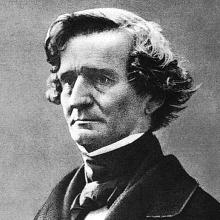

Berlioz symphonies

Hector Berlioz was unquestionably a great and influential composer who wrote operas, liturgical music, songs and choral works and overtures. He also wrote four symphonies, although there are those who say he wrote none at all, and that at best quotation marks should be put around the word symphonies composed by Berlioz. Were they symphonies or were they something else? As one critic wrote:

“These works are not symphonies at all—at least not when measured against the familiar German repertory of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Berlioz’s symphonies frustrate and defy attempts at traditional generic classification by presenting listeners with an exceptional fusion of elements drawn from both opera and symphony.” The result is something completely new—an unorthodox hybrid genre for which Berlioz coined the term "dramatic symphony."

One things that’s immediately obvious about these works is they weren’t given a number. There isn’t a Berlioz Symphony No. 1, or 2, and so on. Instead, each one has a name: Symphonie Fantastique, Harold in Italy, Romeo and Juliet and Grande Symphonie funebre et triomphale.

Before we hear any music, let’s find out a little about Berlioz. He was born in 1803 in a village in south eastern France. His father was a doctor who was first European medic to practise acupuncture. Music wasn’t a big part of his early life. His father gave him a flageolet, a small wind instrument, when he was a boy and he later took flute and guitar lessons. He never learned to play any other instrument.

He had a go at composition when in his early teens but he seemed destined to follow his father’s footsteps into medicine, despite the fact that he hated dissecting bodies. He went to Paris to study medicine but, aided by a healthy allowance from his father, he took advantage of every opportunity to immerse himself in music.

Berlioz was a particularly gifted and insightful writer, and at the age of 20 had a piece published in the music press which defended French opera against the incursions of its Italian rival. He abandoned medicine as soon as he graduated, much to his parents’ chagrin. They suggested the law as an alternative profession, but Berlioz had his heart set on music as a career. When he was 23 he was enrolled in the Paris Conservatoire and the rest is history.

I’m not going to do the music chronologically, and want to start with Harold in Italy, his Opus 16 and the second symphony he wrote. It’s an unusual work in that Berlioz described it as a symphony in four parts with viola obbligato. It’s often referred to as a hybrid of a symphony and a concerto, although there is very little scope for virtuosity in the viola parts.

Needless to say, there’s a story about this work. Paganini encouraged Berlioz to write it. He had acquired what he described as a “superb viola”, a Stradivarius, and told Berlioz; “But I have no suitable music. Would you like to write a solo for viola? You are the only one I can trust for this task."

Berlioz began "by writing a solo for viola, but one which involved the orchestra”. When Paganini saw the sketch of the allegro movement, with lots of rests in the viola part, he told Berlioz it simply would not do. "There's not enough for me to do here,” he told Berlioz. “I should be playing all the time". ‘What you want is a viola concerto’, said Berlioz, suggesting Paganini would be better writing one himself. They then parted, with Paganini more than a tad miffed.

And so Berlioz went alone, and the work was premiered in 1834. Paganini did not hear the work he had commissioned until 1838; then he was so overwhelmed by it that, following the performance, he dragged Berlioz onto the stage and knelt and kissed his hand before a cheering audience and applauding musicians.

A few days later he sent Berlioz a letter of congratulations, enclosing 20,000 francs.

The work is based on a poem by Byron, Childe Harold. Berlioz wrote:

My intention was to write a series of orchestral scenes, in which the solo viola would be involved as a more or less active participant while retaining its own character. By placing it among the poetic memories formed from my wanderings in the Abruzzi, I wanted to make the viola a kind of melancholy dreamer in the manner of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

That said, there is also something autobiographical about this piece, as there is with the Symphonie fantastique.

The first movement, Harold in the Mountains, refers to the scenes that Harold, a melancholic character, encounters in mountains. It’s the movement I featured when I did in a programme of music inspired by mountains.

Berlioz won the Prix de Rome of 1830, and as a result lived and worked in Italy for a couple of years. The impressions he derived from his wanderings in the country to permeated many of his compositions, including this one.

The second movement, which you will hear now, is March of the Pilgrims Singing their Evening Prayer, and paints a lush and romantic picture of Harold accompanying a group of pilgrims through the mountains. This movement was encored at the symphony’s premiere.

Next up is the fourth symphony Berlioz composed, his Grande Symphonie funebre et triomphale, The Funeral and Triumphal Symphony.

Berlioz was the first major composer who was not an instrumentalist to some degree. The orchestra was his instrument, and he liked to use it in a big, epic fashion. He had little time for chamber works, despite the fact they were hugely popular at the time, preferring large-scale orchestral and choral works.

His magnum opus, the opera The Trojans, is so big, long and exhausting that today it is often performed as two separate operas; His Te Deum, for which he would place the orchestra and chorus, which included a children’s choir, at opposite ends of the church, is a such a big work that it includes two instrumental movements which are not always included in modern performances; and his Requiem uses a massive orchestra, with the premiere using 950 performers.

As for his Grand Symphonie, well, it’s an over-the-top piece of ceremonial music. It’s 1840 and the French Government commissioned Berlioz to write a symphony marking the 10th anniversary of the Revolution which brought Louis-Philippe 1 to power. Berlioz wasn’t a fan of the new regime but couldn’t turn down the 10,000 francs he was offered to write this piece.

At first called the Symphonie Militaire, this symphony was originally scored for a wind band of 200 players marching a procession which accompanied the remains of those who had died fighting in the 1830 revolution on their way to be re-interred beneath a memorial column on the site of the Bastille.

The premiere, an actual marching performance, turned out to be predictably chaotic, but the music was an immediate success.

It’s a three-movement work, starting with a funeral match, then a funeral oration and finally a triumphal march.

Berlioz revised the score a couple of years after its premiere, adding an optional part for strings and a chorus. Wagner attended an early performance of this amended work and told Robert Schumann that he found passages in the last movement of Berlioz's symphony so "magnificent and sublime that they can never be surpassed.”

Let’s hear that last movement, called Apotheosis: Glory and Triumph, with a martial air as stirring and proud and French as La Marsellaise.

Now for Romeo and Juliet, a truly astonishing work. You will have gathered from Harold in Italy that Berlioz liked to have some sort of linear narrative in his symphonies. They told a story.

I suppose Beethoven hinted at some sort of narrative with his Pastoral Symphony, which he explicitly said was about rural country life, but he never really followed the idea through as Berlioz did. And this to a large extent set Berlioz apart from his contemporaries and it made him a love-him-or-loathe him figure.

Liszt was a big fan of Berlioz, and Russian composers such as Glinka and Mussorgsky were also admirers. Sir Thomas Beecham was wrote that he considered Mozart to be a greater composer but that his music drew on the works of his predecessors, whereas Berlioz’s works were wholly original. Richard Strauss contended that Berlioz invented the modern orchestra.

However, his work was damned by others. Mendelssohn called Berlioz “a regular freak, without a vestige of talent”. “One ought to wash one’s hands after dealing with one of his scores,” he said. One critic of the day called him a “wretched bungler”. Ravel echoed something Bizet said years earlier when he said he thought Berlioz was “a musician of great genius but little talent”. Debussy called him a “monster”. Pierre Boulez said: “There are awkward harmonies in Berlioz that make one scream.”

I think he was a genius of such vision that his contemporaries didn’t know what to make of him. As Schumann wrote: “There is much in his music that is insufferable, but also a great deal that is extremely intelligent, and even full of genius.”

But maybe the best line I’ve read was something Rossini said on reading the score of the Symphonie fantastique, “What a good thing this isn’t music”.

There was without question some snobbery in the criticism of Berlioz, because he could not play a recognised concert instrument – the guitar hardly counts, does it Mike? More to the point, he never learned to play the piano. So how did he write? Well, he did so more or less blind, or rather deaf, using a quill and occasionally trying out chords or melodies on a guitar.

OK, so to Romeo and Juliet. As a symphony, it’s ground-breaking. Its six movements – and that was novel for a start – has lots of orchestral bits, but it also has choral sections and parts for solo singers. In this respect Berlioz is following the template of Beethoven’s 9th symphony, which was written in 1824, 15 years before Romeo and Juliet.

But it’s not quite like the 9th. It’s a choral symphony which is almost operatic in nature. Berlioz called it a “symphonie dramatique”. One critique I read called it “one of the most gigantic and convincing masterpieces of music-drama". These days it’s called a “programmatic piece”, as is Harold in Italy.

Oh, and it’s long for a symphony – over an hour and a half. A young Wagner attended the premiere, and there’s no doubt he was influenced by this music and its scale.

The whole work was made possible thanks to the 20,000 francs Paganini gave Berlioz. Berlioz, who was always skint, used the cash to pay off some debts and to fund his existence while he wrote Romeo and Juliet.

Berlioz was especially fond of this symphony. He wrote that one movement in particular became a favourite:

If you now ask me which of my pieces I prefer, my answer will be that I share the view of most artists: I prefer the adagio (the Love Scene) in Romeo and Juliet.

The movement is the very heart of the symphony, I suppose emotionally as well as structurally. Here, it’s performed by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra under Michael Tilson Thomas.

In the rest of this programme I’ll deal with Berlioz’s his first “symphony”, Symphonie fantastique, which he wrote in 1830. It’s another good example of a programme symphony: that is, a symphony based on some sort of non-musical narrative. In this case, the narrative was inspired by the crush Berlioz had for an Irish Shakespearean actress, Harriet Smithson, whom he had seen playing Ophelia in Hamlet.

He sent her numerous love letters, all of which went unanswered. In truth, he stalked her incessantly. Berlioz then wrote Symphonie fantastique as a way to express his unrequited love. Harriet did not attend the premiere in 1830, but she heard the work in 1832 and realised Berlioz's genius. The two finally met and were married in October the following.

However, their marriage became increasingly bitter. She was jealous of his success and moved out of their home. They separated after several years of unhappiness. I don’t know how they managed to row. He couldn’t speak English and she couldn’t speak French.

As for the Symphony fantastique, it has five movements, instead of the four, which was the norm at that time. He gave each one a name, in English, Passions, A Ball, Scene in the Fields, March to the Scaffold and Dream of a Night of the Sabbath. In short, it tells the story in music of an artist gifted with a lively imagination who in the depths of despair because of his unrequited love, has poisoned himself with opium.

Liszt was so taken by the symphony that he transcribed the whole lot for piano so that more people could hear it.

There’s more I thought I would say about this work but instead I decided I would let you hear Leonard Bernstein talk about it, at some length I might add.

Let’s now hear the first movement, of the Symphony fantastique without Bernstein’s commentary. It’s performed by the LSO under Sir Colin Davis.

I mentioned Berlioz’s failed marriage. Long after he had separated from Harriet, he continued to financially support her as she gradually descended into an alcohol addiction. She died in 1854 and in that year Berlioz remarried. His new wife, a singer called Marie Recio, died of a stroke in 1862 and Berlioz died at the age of 65 seven years later.

However, long before that happened, and before he married Harriet Smithson, Berlioz fell in love with a 19-year-old pianist called Marie, or Camille, Moke. The couple planned to be married but when Berlioz went to Italy he learnt that she had broken off their engagement and was to marry an older and richer man.

Berlioz came up with an elaborate plan to kill them both, as well as the girl’s mother, and bought pistols, poison and a disguise for the purpose. He came to think better of the idea and put the affair behind him.

Berfore we close, let’s hear more from the Symphonie fantastique. This is the fourth movement, the March to the Scaffold.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Berlioz symphonies playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.