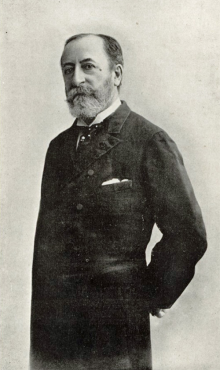

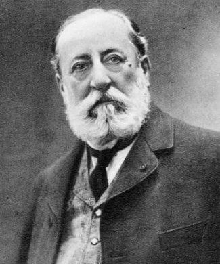

Camille Saint-Saëns

Charles-Camille Saint-Saëns was undoubtedly one of the most significant cultural figures in 19th century France. He had a long life – he was born in Paris in 1835 and died in 1921 – and a long musical career which really encompassed the Romantic era and its transition into the modern age. If you think of it, he was born less than a decade after the death of Beethoven, and was still composing three years after Debussy died. But by the time Saint-Saëns died his reputation was something of a fuddy-duddy. He was called with an element of sarcasm, "the grand old man of French music".

He was a prolific composer, pianist and organist and, like many famous composers, a child prodigy. As a boy, he was hailed as the French Mozart. Saint-Saëns was raised by his widowed mother and her aunt who introduced him to the piano and gave him his first lessons. He gave his first public concert at five, accompanying a Beethoven violin sonata on the piano. When he was 10 he gave a concert that included Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3.

He was very much classically inclined as a musician but, as an admirer of Liszt and Wagner, he was in his earlier years influential in promoting new music. His vast and versatile output included symphonies, concertos, chamber music often for unusual combinations of instruments, operas and songs. Liszt, by the way, described Saint-Saëns as "the greatest organist in the world".

However, his performance style was described as ‘restrained, subtle and cool’. He was one of the first pianists to experiment with recordings, and was in fact the earliest-born pianist to ever make a recording of his work.

I thought I would do this programme chronologically and start where his career as a composer started, with his Opus 1 – Three Pieces for Harmonium. Did any other composer begin writing music for the harmonium, I wonder? He wrote this when he was 16.

Saint-Saëns made his concert debut at the age of 10, studied organ and composition at the Paris Conservatoire, got a job as a church organist and, later, made a good living as a freelance pianist and composer. Saint-Saëns also held a teaching post in Paris for just under five years, and his students include Gabriel Faure, among whose own later pupils was Maurice Ravel. Both of them were strongly influenced by Saint-Saëns, whom they revered as a genius.

Saint-Saëns composed his Opus No. 2, his first symphony, at the age of 16, while he was working as a church organist. It features military fanfares and brass and percussion sections and really caught the mood of the times in the wake of the rise to power of Napoleon II. This is the second movement of his Symphony No. 1, and the Radio Luxembourg Symphony Orchestra.

Saint-Saëns’ formidable intellect was not limited to music. In fact, to an extraordinary degree, Saint-Saëns mastered every field of endeavour to which he turned his eclectic mind. He had a profound interest in - and knowledge of - geology, botany, butterflies, astronomy, archaeology and maths. He was a poet and playwright of some distinction. He could master foreign languages with ease. And he enjoyed discussions with Europe's finest scientists and wrote numerous academic articles about acoustics.

However, he was, primarily, a musician. In 1858, when he was 23, he landed a top job: organist of La Madeleine, the official church of the French Empire. Rossini, Berlioz and Liszt all spotted his talents as a musician.

The next piece you are going to hear is from his Piano Concerto No.2, written in just three weeks 1868. It’s a well-known piece with what has been called “capricious changes in style”. As someone once said: “It begins with Bach and ends with Offenbach.”

This is Romain Descharmes and the Malmo Symphony Orchestra playing the third movement.

Next you are going to hear his Introduction and Rondo Capriccioso, with Zubin Mehta conducting the New York Phil and Itzhak Perlman playing the violin. You may well be familiar with the piece, which really is a showpiece.

Saint-Saëns composed his _Cello Concerto No. 1 _in 1872, when he was 37 years old. He wrote it for the Belgian cellist August Tolbecque and many composers, including Rachmaninoff and Shostokovich, consider it to be the greatest cello concerto ever written. Saint-Saëns broke with convention in writing the concerto. Instead of using the normal three-movement concerto form, he structured the piece in one continuous movement which is split into three distinct sections. This is the opening section played by Jacqueline du Pre with her husband Daniel Barenboim conducting the New Philharmonia Orchestra.

Two years after that piece was published Saint-Saëns wrote Danse Macabre, a tone poem for orchestra that started life as a song for voice and piano. Later, he replaced the vocal line with a violin part and added the full orchestra.

When it was premiered, it was immediately encored in full – and that’s not something that happens too often. However, it wasn’t universally acclaimed. One critic wrote of the “horrible screeching” of the solo violin, and the use of the xylophone prompted some concern. Today, it’s seen as one of his masterpieces. This is the RSNO under Alexander Gibson.

To be honest, I’ve never really liked it. It gives me the creeps, but then that’s doubtless what’s intended from a piece that’s supposed to evoke skeletons dancing in a graveyard.

Next you are going to hear Julian Lloyd-Webber and the English Chamber Orchestra perform, with some haste I think, having listened to a number of recordings, Saint-Saens’ Allegro appassionato.

It’s the first piece Saint-Saëns wrote after he got married in 1875. He was 40 and his bride, Marie Truffot, was the 19-year-old sister of one of his pupils. There was no honeymoon and after the ceremony they returned to the house in Paris which the composer shared with his mother.

The couple had two sons, both of whom died in infancy, one of them falling from the fourth-floor window of a flat when he was two. He blamed his wife for the accident, which was followed just six weeks later by the death from pneumonia of their six-month-old son. Saint-Saëns, influenced by his mother, blamed his wife for their deaths.

Six years later the couple went on holiday. He mysteriously disappeared from his hotel and a few days later she received a letter from him saying that he would not be returning. They never saw each other again but never divorced. She lived until 1950, dying at the age of 95.

So, Allegro appassionato, another of Saint-Saens’ cello showpieces.

In 1877, Saint-Saens had a major operatic success with Samson et Dalila, his one opera to maintain a place on the repertoire today. Saint-Saëns later wrote:

A young relative of mine had married a charming young man who wrote verse on the side. I realized that he was gifted and had in fact real talent. I asked him to work with me on an oratorio on a Biblical subject. 'An oratorio!', he said, 'no, let's make it an opera!', and he began to dig through the Bible while I outlined the plan of the work, even sketching scenes, and leaving him only the versification to do. For some reason I began the music with Act 2, and I played it at home to a select audience who could make nothing of it at all.

The young relative was a man called Ferdinand Lemaire, the husband of one of his wife’s cousins.

Saint-Saëns began writing the opera, for some reason, with Act II, and it’s from that act that the next piece comes. It's Mon couer s’ouvre a ta voix, Softly awakes my heart. It’s sung as Delilah attempts to seduce Samson into revealing the secret of his strength, and it’s performed here by Maria Callas.

It will be followed by another piece from Samson et Dalila, the sumptuous Danse Bacchanale, from the third act. It will be played by the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy.

Samson and Delilah faced quite some problems with the censors because of prejudice against portraying Biblical characters on the stage. When it was due to be performed in London, the Lord Chamberlain slapped a ban on the whole opera, stopping all but concert performances until 1909, some 30 years after its premiere.

Saint-Saëns wrote his Violin Concerto No. 3 while in Spain in 1880. Indeed, he wrote it for the greatest Spanish violinist of the century, Pablo de Sarasate. He had been playing around with the lay-out of movements in his concertos but here he returned to the orthodox fast-slow-fast pattern. This is the opening movement, with Itzhak Perlman again.

Saint-Saëns was a pianist so maybe we should hear a piano piece, Wedding Cake, which he wrote as a wedding present for a pianist friend in 1885. The pianist here is Michel Plasson.

It’s been said that Saint-Saëns was at the peak of his artistic career when, at the age of 51, he wrote his third symphony in 1886. It is also popularly known as the Organ Symphony, even though just two of the four sections use the pipe organ. I’ll explain more about that later.

After writing it, Saint-Saëns said: "I gave everything to it I was able to give. What I have here accomplished, I will never achieve again." The composer seemed to know it would be his last attempt at the symphonic form, and he wrote the work almost as a type of "history" of his own career: virtuoso piano passages, brilliant orchestral writing and the sound of a cathedral-sized pipe organ.

The symphony was commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Society in England, and the first performance was given in London in May 1886, conducted by the composer. After the death of his friend Franz Liszt two months later, Saint-Saëns dedicated the work to Liszt's memory.

This is Leonard Bernstein and the New York Phil with the symphony’s fourth and final movement. Or rather, it isn’t. For though the symphony appears to have the usual four-movement structure, Saint-Saëns thought he created a novel two-movement symphony. That said, he did acknowledge that it could easily be seen as having four movements.

A curious thing about the symphony is that it features the piano scored for both two and four hands.

Saint-Saëns was very close to his mother, who had opposed his marriage. When she died at the age of 79 in 1888, two years after the last piece was premiered, he fell into a deep depression, even contemplating suicide for a time. Unable to face living in the family apartment, he got rid of most of his possessions and led a nomadic life until his death. By the end of his life in 1921, he made 179 trips to 27 countries, often travelling under a false name. His professional engagements took him most often to Germany and England; for holidays, and to avoid Parisian winters which affected his weak chest, he favoured Algiers and Egypt.

Saint-Saëns composed what is commonly known as his Egyptian Concerto, his Piano Concerto No. 5, in Luxor in 1896 while on one of his frequent winter holidays in Egypt. But the concerto is also called the Egyptian because the music is among his most exotic, displaying influences from Javanese, Spanish and Middle-eastern music. Saint-Saëns himself was the soloist at the première, which was a huge success.

Here, the Malmo Symphony Orchestra play the finale of what was Saint-Saens’ last piano concerto, with Romaine Descharmes at the piano.

In 1908, Saint-Saëns became the first famous composer to provide a score to a feature film. The 18-minute-long film, ‘The Assassination of the Duke of Guise’, was made by a team who also encouraged well-known stage actors to perform in their films to give them some kudos. Saint-Saëns later developed his music into a concert work - his Opus 128 for strings, piano and harmonium. Here’s the finale.

Saint-Saëns fell badly out of fashion in his later years. His music was regarded with some condescension in his homeland, even though in England and the United States he was hailed as France's greatest living composer well into the 20th century.

And 20th century music wasn’t to his taste either; after taking in the first concert performance of the Rite of Spring he said he thought Stravinsky was insane. He was outspoken in his dislike of Richard Strauss and Brahms. Not only did he denounce new music; during the First World War he tried to organise a boycott of all German music. Saint-Saëns also had a particular animosity with Claude Debussy who once said somewhat cruelly, “I have a horror of sentimentality and cannot forget that its name is Saint-Saëns.”

In the last two decades of his life, he was largely a loner who cared more for his dogs than any human. During this time, as he became more critical of his contemporaries, his reputation was severely damaged.

In 1921, at the age of 86, he went to Algiers intending to winter there and died of a heart attack in the arms of his manservant. He was given a state funeral.

Well, I have managed to say quite a bit about Saint-Saëns without mentioning his best-known work, Carnival of the Animals. I’m going to talk a bit more about this work in another programme, and I’m not in this programme going to use the best-known part of it. He wrote Carnival of the Animals in 1886 as a suite in 14 movements, with each movement depicting an animal or animals. You are going to hear three movements, The Introduction and Royal March of the Lion, Hens and Cocks, and Wild Asses.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Camille Saint-Saëns playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.