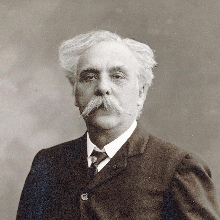

Gabriel Fauré

I found this programme about Gabriel Fauré particularly difficult to put together because I had two conflicting challenges: choosing music that could be said to sum up the composer and putting together a musically diverse programme. You see, throughout his life Fauré was criticised for failing to embrace large-scale works, resolutely refusing to move away from chamber music and elegant choral miniatures. However, I had no difficulty at all choosing my first piece. Let’s hear it now: an elegant choral miniature.

That was Fauré’s Cantique de Jean Racine, The Hymn of Jean Racine, performed by the Choir and Orchestra of Paris conducted by Paavo Jarvi. Jean Racine was a 17th century dramatist who wrote the hymn, based on a much older Latin one, and Fauré wrote that music when he was just 19.

Fauré was the youngest of six children. He was born in south west France in 1845 into a cultured but not particularly musical family. He said:

"I grew up, a rather quiet well-behaved child, in an area of great beauty. But the only thing I remember really clearly is the harmonium in that little chapel. Every time I could get away I ran there...I played atrociously...but I do remember that I was happy; and if that is what it means to have a vocation, then it is a very pleasant thing."

He showed aptitude for music as a young boy. Apparently, an old blind woman, who heard the boy play the harmonium told his father of Fauré's gift for music and after much thought the father placed his son, at the age of nine, in a school of church music in Paris, where he was trained in piano, theory, composition, and classical languages. Weekly choir singing was part of the curriculum. Helped by a scholarship from the bishop of his home diocese, Fauré boarded at the school for 11 years. The régime was austere, the rooms gloomy, the food mediocre, and the required uniform elaborate. The musical tuition, however, was excellent. Fauré's teacher in advanced piano was someone who became a lifelong friend, Camille Saint-Saëns, who encouraged him to compose.

Fauré won many prizes while at the school, including a first prize in composition for piece you just heard. The Cantique was premiered in 1866 with Cesar Franck, to whom Fauré dedicated it, conducting. Although the Cantique is just five minutes long, it confirmed Fauré’s status as one of France’s brightest musical prospects.

I now want you to hear two pieces featuring the cello, with Mischa Maisky performing. The first is called simply Tristesse, Sadness, and was actually written for voice and piano in 1873. It was the second of a set of three pieces, called simply Three Songs.

I think there is a catchiness to this music that to me evokes Paris. Indeed, the words of the song talk about cheerful drinkers and lovers. The second piece you will hear is called Les Berceaux, The Cradles, and was written six years later. Again, it’s one of a set of three songs, and this one talks about women at the quayside rocking their babies’ cradles while they watch their menfolk sail off, tempted by “horizons that lure”.

A great deal of Fauré’s work sounds like that. It is languid, sometimes even limpid, and has an easy charm. It’s been described as intimate music, and I’ve read of Fauré being described as a “civilised composer”. Some people also see him as the French Elgar. Indeed, the two men had a great deal of respect for each other. Fauré attended the London premiere of Elgar’s 1st Symphony and dined with him after the concert. Elgar in turn lobbied to have Fauré’s work played in England. Aaron Copland wrote that he felt Fauré’s work possessed “all the hallmarks of the French temperament: sensibility, impeccable manners and classic reserve.” Indeed, that could easily describe Fauré himself. He was congenial and mild-mannered.

From 1903 to 1921, Fauré regularly wrote music criticism for the newspaper Le Figaro, a role in which he was not at ease. It's thought that Fauré's natural kindness and broad-mindedness meant he tended to emphasise the positive aspects of a work and not be critical enough.

Anyway, on leaving music school Fauré got a job as a church organist in Rennes and in his four years there topped up his income by taking private pupils. He was bored there and had an uneasy relationship with the parish priest, who correctly doubted Fauré's religious conviction. Fauré was regularly seen stealing out during the sermon for a cigarette, and in 1870, when he turned up to play at Mass one Sunday still in his evening clothes, having been out all night at a ball, he was asked to resign.

On the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war in 1870 he volunteered for action, took part in the Siege of Paris and in several other engagements, and was awarded the Croix de Guerre. After the war, he went back to Paris and was appointed choirmaster at the Église Saint-Sulpice under the composer and organist Charles-Marie Widor. During some services, Widor and Fauré improvised simultaneously at the church's two organs, trying to catch each other out with sudden changes of key.

Fauré regularly attended Saint-Saëns's musical salons and those of the famous opera singer Pauline Viardot, a mezzo-soprano. Indeed, Saint-Saëns introduced Fauré to the singer Pauline and her family, and Fauré spent the next several years courting her daughter Marianne. In 1877 he proposed marriage. Marianne accepted – then changed her mind. She seems to have become afraid of Fauré. Accounts of this time show the young composer suffering bouts of intense depression, severe migraines and dizzy spells in which he had to lean against walls to stop himself falling.

In 1874, Fauré went to work as deputy to the principal organist, Saint-Saens, in the église de la Madeleine, the largest Catholic church in Paris, where Chopin’s funeral service was held 25 years earlier. By now, he was composing a great deal, got to know Wagner, Bizet, Lalo and Liszt and developed what became a lifelong love of foreign travel. He would go to Germany to spend time with Liszt and to see Wagner’s operas. Fauré admired Wagner and had a detailed knowledge of his music, but he was one of the few composers of his generation not to come under Wagner's musical influence.

In 1883, he married Marie Fremiet, the daughter of a leading sculptor and the couple had two sons. Actually, Fauré may well have had more children: he was said to be very attractive to women and had several extra-marital affairs. Someone wrote at the time that “his conquests were legion in the Paris salons”. Fauré apparently hated domestic life. To support his family, he spent most of his time in running the daily services at the Madeleine and giving piano and harmony lessons. His compositions earned him a negligible amount, because his publisher bought them outright, paying him an average of 60 francs for a song, and Fauré received no royalties.

Although he was an organist, Fauré much preferred the piano and wrote extensively for it. Let’s now hear the second movement, a lighter-than-air, playful scherzo, from his Piano Quartet No. 1, which he wrote towards the end of his engagement with Marianne Viardot. It’s one of only two pieces he wrote for the conventional piano quartet of piano, violin, viola and cello. I have chosen this movement because it’s one of Fauré’s rare virtuoso pieces – he tended to shy away from showmanship in music. However, I probably should have chosen the third, slow movement, which is one of his best and which is thought to reflect the sadness in his life after his relationship with Marianna Viardot broke down.

This is the Emerson String Quartet, who are based in New York and who have been one of the world’s leading chamber ensembles for more than 40 years.

Now another piano-based piece written around the same time as that last piece: that is, around 1879. Fauré dedicated this work to Saint-Saens. It was written as Fauré’s most substantial work for solo piano but at Liszt’s suggestion Fauré wrote the version you are going to hear, for piano and orchestra.

Fauré first conceived the music as a set of individual pieces but then decided to make them into a single work by carrying the main theme of each section over into the following section. The Ballade has been described as “a reminder of halcyon, half-remembered summer days and bird-haunted forests”.

However, there’s another very un-PC description of the piece by Debussy. He once reviewed a performance of the work and compared the music with the attractive soloist, straightening her shoulder-straps during the performance: "I don't know why, but I somehow associated the charm of these gestures with the music of Fauré himself. The play of fleeting curves that is its essence can be compared to the movements of a beautiful woman without either suffering from the comparison.”

It’s hard to believe but Liszt, who as a pianist was an absolute wizard, technically speaking, said that he found that piece too difficult to play.

I now want you to hear part of one of Fauré’s best works, his Requiem, performed by The Sixteen and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields. Fauré composed his Requiem between 1887 and 1890. He was an agnostic and once said he wrote the Requiem solely for his pleasure. The Requiem is a lament for the dead and Fauré’s is calm, peaceful and serene. It has been described as "a lullaby of death" because of its predominantly gentle tone. Fauré wrote:

“Perhaps I have instinctively sought to escape from what is thought right and proper, after all the years of accompanying burial services on the organ! I know it all by heart. I wanted to write something different."

The Requiem was criticised at the time for reflecting an insufficient fear of death. Fauré maintained that he had a much more optimistic view of mortality than other composers. He saw death as a "happy deliverance, an aspiration towards later happiness, rather than as a painful experience." He said:

"Everything I managed to entertain by way of religious illusion I put into my Requiem, which moreover is dominated from beginning to end by a very human feeling of faith in eternal rest."

We are going to hear two parts of his Requiem, first the Pie Jesu followed by In Paradisum.

The Requiem was performed at Fauré’s own funeral in 1924. However, he wrote the piece most definitely for liturgical use unlike. It does not ask to be a concert work like, say, Verdi’s Requiem.

Fauré suffered from severe bouts of depression from his 30s onwards, so much so that friends were concerned about his health. However, in his late 40s he started an affair with a woman called Emma Bardac and dedicated one of his best-known works, the Dolly Suite, to her daughter. The affair inspired a burst of creativity and gave Fauré a new lease of life. In the 1890s he was appointed inspector of the music conservatoires in the French provinces, a job which took him all over the country. Later, he became Professor of Composition at the Paris Conservatoire, where he taught were Maurice Ravel and Nadia Boulanger among others. Ravel always remembered Fauré's open-mindedness as a teacher. Having received Ravel's string quartet with less than his usual enthusiasm, Fauré asked to see the manuscript again a few days later, saying, "I could have been wrong".

Fauré was the subject of virulent criticism while in this post: not being a former student of the Conservatoire and having never won a Prix de Rome, his nomination as director was at first strongly contested. He was then criticised on the way he carried out his duties, his behaviour considered too serious and too severe, even leading to the resignation of certain professors.

Among the pieces he wrote at this time was the incidental music for Maurice Maeterlinck’s play Pelleas et Melisande, about the forbidden and doomed love of its title characters. Fauré was once of four leading composers who were inspired to write music to accompany this play: Debussy’s is better known than the versions written by Schoenberg and Sibelius.

Fauré himself conducted the premiere of the suite in the Price of Wales’ Theatre in London in 1898. It comes in four movements, and we are going to hear the entire suite played by the Academy of St Martin in the Fields conducted by Sir Neville Marriner.

Fauré embarked on his finale love affair in 1900, with a pianist called Marguerite Hasselmans. He put her up in a Paris apartment and was quite open about their relationship.

While he also became much more widely known as a composer, running the Conservatoire left him with no more time for composition than when he was struggling to earn a living as an organist and piano teacher. As soon as the working year was over, in the last days of July, he would leave Paris and spend the two months until early October in a hotel, usually by one of the Swiss lakes, to concentrate on composition.

I want to go back in time now and play more of his piano work, his Trois Romances sans paroles, Three Romances Without Words, which he wrote when he was in his late teens. They were his first piano pieces to be published, and here they are played by Nicolas Stavy.

The outbreak of World War One almost stranded Gabriel Fauré in Germany, where he had gone for his annual composing retreat. He managed to get from Germany into Switzerland, and thence to Paris. He remained in France for the duration of the war. When a group of French musicians led by Saint-Saëns tried to organise a boycott of German music, Fauré dissociated himself from the idea. Art was international, he maintained.

Like Beethoven, Smetana and Vaughan Williams, Fauré suffered from deafness towards the end of his life, and this forced him to resign from the conservatoire in 1920. He had to – he was completely deaf by this stage. Indeed, he never heard a note of his last major work, his only full-length opera, Penelope. He died of pneumonia in 1924, at the age of 79, and was given a state funeral. The day before he died, he announced to his family: "I have done what I could, so God be my judge."

One of his last major commissions was to write incidental music for what was called a theatrical entertainment for the Monte Carlo Theatre. He produced eight movements, which he later distilled into just four for his Masques et Bergamasques Suite, which was described as Fauré’s “farewell to the orchestra”.

A masque, of course, is a masked ball. As for Bergarmeques, it comes from the Italian Bargamasco, a dance from the city of Bergamo, where I happened to spend a couple of days last weekend.

As you have heard, much of Fauré’s earlier work was restrained, wistful almost, but this is a bit weightier.

Let’s hear the suite’s four movements, played by the Basel Symphony Orchestra.

Before we go, I thought you should hear something that is more quintessentially Fauré. This is Sheku and Istaka Kanneh-Mason playing an arrangement for cello and piano of Fauré’s Apres un reve, After the Dream, which he wrote as the first of a set of three melodies for voice and piano between 1870 and 1877. You heard one of the other pieces earlier this morning.

Here’s what was written about Fauré on the 100th anniversary of his birth: “More profound than Saint-Saëns, more varied than Lalo, more spontaneous than d'Indy, more classic than Debussy, Gabriel Fauré is the master par excellence of French music, the perfect mirror of our musical genius.”

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Gabriel Fauré playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.