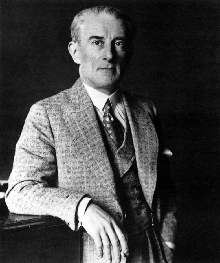

Maurice Ravel

Maurice Ravel ranked as one of the outstanding composers of music of the 20th century. He wrote in many forms, for piano, voice, opera, ballet, chamber ensembles and orchestra. Perhaps his most significant contribution was his mastery of instrumentation.

I don’t suppose I’ve been able to conceal the fact that Shostakovich is my favourite composer. Ravel comes a very close second. I feel that a lot of his work sparkles. It’s inventive and sometimes daring. Just think of Tzigane, the violin piece he wrote of Jelly d’Aranyi, which seems to emit electricity, or the Bolero. Who else would have even thought of writing the Bolero? We are so familiar with it that we take it for granted, but it’s a truly daring work. As someone shouted at its premiere, “Au fou, au fou!”, “The madman, the madman!” The Bolero was performed for the first time in 1928 and became an immediate success – much to the surprise of Ravel, who regarded it with condescension, said it consisted wholly of “orchestral tissue without music” and was certain that orchestras would refuse to play it.

Ravel was often very negative about his output yet in the two decades between the wars, he was regarded as the greatest living French composer.

He was born in 1879 just a few miles from the Spanish border to a Basque mother and a Swiss father who invented an internal combustion engine and a ‘whirlwind of death’ circus machine. It was a musical family and when the family moved to Paris Ravel attended the conservatoire there, having had piano lessons from the age of seven. He won first prize in the conservatoire’s piano competition yet it’s said he didn’t really stand out as a student. The young Ravel was captivated by new music coming out of Russia, particularly Rimsky-Korsakov’s. He was also introduced to Erik Satie, whose distinctive personality and unorthodox music had a strong influence on Ravel.

By 20, Ravel was something of a dandy - meticulous about his appearance and demeanour. He was a lifelong smoker and enjoyed good food, fine wine, and spirited conversation. As it happens, some have felt that his meticulous nature was reflected in his composition. I’ve seen his work described as “a blend of sober refinement and luxuriant exoticism”. Stravinsky described him as “the most perfect of Swiss clockmakers”.

As a musician, Ravel drew inspiration from many sources and his work sometimes blurred boundaries, for example between serious and light music, or between what might be regarded as classical music and jazz. Speaking of his own aims and ideals, he once said:

If I ever did a perfect piece of work I would stop composing immediately. One just tries, and when I have finished a composition I have 'tried' all I can; it's no use attempting anything more in the same direction. One must seek new ideas.

As for his personality, his dandified aristocratic appearance and dry humour kept most people at bay, apart from a few friends. And as for relationships, there’s almost no trace. In the end Ravel seems to have preferred the company of the mechanical birds and music-boxes he kept in his house in the country.

Ravel studied composition under Faure at the conservatoire and while there he wrote his first piece to attract widespread attention, his Pavane pour une infant defunte (Pavane for a Dead Princess). It was written as a piano piece for his patron, the Princesse de Polignac, whose father was Isaac Singer, the famous sewing machine manufacturer. Ravel was at pains to point out that, despite the title, the piece is not a funeral lament but “rather an evocation of the pavane, which is a slow dance popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, that might have been danced by such a little princess as painted by Velazquez”.

This is the Pavane, played by Bertrand Chamayou.

By the way, Ravel intended that piece to be played extremely slowly – more slowly than almost any modern interpretation. He published an orchestral version of the Pavane in 1910, 10 years after the original.

From the start of his career, Ravel appeared indifferent to blame or praise. He was a notorious perfectionist who worked very slowly. The only opinion of his music that he truly valued was his own. It’s said that at 20 years of age he was "self-possessed, a little aloof, intellectually biased, given to mild banter”.

In 1902, when he was just 23, his opera Pelleus et Melisande was premiered. Saint-Saens was among the work’s biggest critics but it didn’t seem to bother Ravel. In fact, Ravel attended all 14 performances in the first run of the opera in Paris.

Let’s hear more music now, and a piece with a Spanish name, Alborada del gracioso, The Jester’s Morning Song. It’s from a five-movement suite called Miroirs, Mirrors, written in 1904 and 1905. It was written for piano but you are going to hear an orchestral version performed by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra conducted by Daniel Barenboim.

With several major compositions under his belt, Ravel took to teaching for a spell. In fact, in the 1920s George Gershwin asked him for lessons. Ravel, after serious consideration, refused, on the grounds that they "would probably cause him to write bad Ravel and lose his great gift of melody and spontaneity". The best-known composer who studied under Ravel was probably Vaughan Williams, who was his pupil for three months in 1907–08.

Next you are going to hear something from the one-act opera L’heure espagnole, The Spanish Hour, meaning something more like ‘How they keep time in Spain’. This is a farce, completed in 1907, set in Spain in the 18th century. It’s about a clockmaker whose unfaithful wife attempts to make love to several men while he is away, leading to them hiding in, and eventually getting stuck in, her husband's clocks. You’re going to hear the introduction, with its ticking clock, performed by the Orchestre National De Lyon with Leonard Slatkin conducting.

Immediately after that you will hear yet another Spanish-inspired piece, Rapsodie espagnol, composed at around the same time. It’s one of Ravel’s first major works for orchestra and you are going to hear the fourth movement, Feria, performed by the French National Radio Orchestra under Andre Cluyens.

We’ve heard something from a Ravel opera; now we’ll have a piece he wrote for his ballet, Daphnis et Chloe, which he described as a choreographic symphony. Ravel began work on it in 1909 after a commission by Diaghilev, and it was premiered in Paris in 1912. It’s Ravel’s longest work and is based on a story by a 2nd century Greek writer. It tells the story of a baby boy and girl who are discovered separately, two years apart, alone and exposed on a Greek mountainside. Taken in by a goatherd and a shepherd respectively, they grow to maturity unaware of one another's existence.

Here’s Anime, a dance from the ballet, with Valery Gergiev conducting the LSO.

During his years at the Conservatoire, Ravel had tried and failed five times to win the prestigious Prix de Rome – a scholarship to study in Italy for France’s leading artists and musicians. This lack of recognition became known as the ‘Ravel Affair’, and great controversy was stirred up in the Parisian Press, and by Ravel’s friends and colleagues.

When World War One broke out he tried to join the army but he was rejected because, of all things, at just 7 stone 7lbs, he was too light. He then thought he could be an aerial bombardier, that is to say the guy who dropped bombs from aircraft, but was rejected for that because he had a minor heart ailment. In time, he was declared fit for service in the military supply department as a truck driver. While returning from a brief stint of leave in mid-August 1916, he contracted dysentery and was hospitalised. Just as he was getting over the dysentery, he was diagnosed with a hernia and operated on. For him, the war was over.

For a short period in the war, Ravel was effectively blacklisted and his music was not performed in France. This was because of his refusal to support a ban on foreign music, something, which had powerful backers in the French musical establishment. But Ravel's reputation as one of France’s leading composers prevailed. In 1920 he was offered membership of the Légion d'Honneur. He very publicly refused it.

Ravel was certainly close to the action in the front, particularly during the Battle of Verdun in 1916, and there’s no doubt the war left a mark on him. In 1917 he completed Le Tombeau de Couperin, a solo piano suite in six movements, with each movement dedicated to a friend, or friends, killed in the war. You are going to hear the prelude to the suite. This piece was written in memory of a First Lieutenant, Jacques Charlot.

Ravel produced an orchestral version of the piano piece you just heard in 1920, three years after he wrote the piano solo version.

And 1920 saw the premiere of what I feel is one of Ravel’s most interesting and dramatic works, La Valse, The Waltz. It’s interesting because it isn’t a waltz: it’s about the waltz. Ravel was a big fan of the waltz. He liked the dance’s “wonderful rhythms” and spoke of the joie de vivre it delivered. As early as 1906 he wrote of his plans to write a piece in tribute to the waltz and to Johann Strauss 11. His original idea was to call the piece ‘Vienna’. As it happened, Ravel didn’t return to his idea until 1919, prompted by a commission from Sergei Diaghilev.

Ravel worked on three versions of La Valse simultaneously: one for a large symphony orchestra, one for piano solo, which was probably intended as a rehearsal aid, and a version for two pianos. The latter was the one in which La Valse was first performed for Diaghelev, for whom Ravel had previously composed the music for the ballet Daphnis et Chloé. But Diaghelev, who had hopes for another ballet, rejected La Valse, saying it was a masterpiece but only a “portrait of a ballet”, not a real ballet. His reaction put an end to the relationship between the two. When the two men met again several years later Ravel refused to shake Diaghelev’s hand, and Diaghelev, who was offended, challenged Ravel to a duel – which never took place. That was their last encounter.

Ravel conceived La Valse entirely as a visual work and even wrote a detailed programme for its first part. It read:

Through whirling clouds, waltzing couples may be faintly distinguished. The clouds gradually scatter: one sees […] an immense hall peopled with a whirling crowd. The scene is gradually illuminated. The light of the chandeliers bursts forth […]. Set in an imperial court, about 1855.

La Valse opens softly as if to create the impression of a mist, and various bits of melodies slowly appear. The waltz goes through various mood changes: from elegant to pompous; slightly melancholic, and so on. But towards the end it all goes downhill and the waltz’s character becomes almost hysteric. The music explodes into a violent climax almost as if the waltz itself is destroyed. At least, that’s how La Valse is generally interpreted.

But there’s another interpretation. When Ravel wrote La Valse, World War I had just ended, and Vienna was no longer a city of glory. According to one review, La Valse as a symbol for “the birth, decay and destruction of a musical genre through a new, nightmare-ish musical language. Ravel saw the waltz as a symbol of old Europe with all its beauty, dignity, and civility. But in time something got lost and it all began to descend into ugliness, instability and chaos.

Here then is La Valse, performed by the French National Radio Orchestra under Andre Cluytens.

In 1922, Ravel completed his now well-known arrangement of Mussorgsy’s Pictures at an Exhibition. Ravel had a reputation as a master orchestrater, and though Mussorgsky's piano writing in the suite is as picturesque as can be, achieving mystery, frenzy, humour, and grandeur, it is a work that cries out for orchestral colour, and several composers were unable to resist the challenge. The first was a pupil of Rimsky-Korsakov, Mikhail Toushmalov in 1891, and in 1915 Sir Henry Wood came up with a picturesque arrangement, but the most popular arrangement is Ravel's. Ravel was commissioned by the Russian conductor Serge Koussevitzky, who knew of Ravel's admiration for Mussorgsky.

Ravel spent hours interviewing instrumentalists to discover new possibilities the piece offered, and he was the perfect candidate to turn the piano suite into a concert-hall showpiece. In every movement, he selected precisely the right combination of instruments needed to duplicate Mussorgsky's original atmosphere.

He did the orchestration for art, to be sure, but he also did it for money. He earned a considerable sum from this work, even though it was condemned by Leopold Stokowski as being “too French”.

Money was important to Ravel. In 1928 he went on a playing and conducting tour of the United States. His fee was a guaranteed minimum of $10,000 and a constant supply of Gauloises cigarettes and he took in all the jazz he could. He commented:

The most captivating part of jazz is its rich and diverting rhythm. ... Jazz is a very rich and vital source of inspiration for modern composers and I am astonished that so few Americans are influenced by it.

And so when in the next two years he composed his G-major piano concerto he infused it with jazz harmonies and rhythms.

I couldn’t choose which of the three movements to use so I thought I would let you hear the entire concerto. The first movement clearly shows strong jazz and blues influences. You will be reminded of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. The second is a very pleasant and tranquil adagio and the third fairly rattles along with some intensity.

Ravel wanted to give the first public performance of this new work himself. However, health issues, said to be caused by fatigue, got in the way. Eventually, Ravel offered the premiere and dedicated the concerto to Marguerite Long, a very gifted French pianist and teacher, who premiered it in January 1932. Ravel and Long then started a tour of 20 cities in Europe, where the work was received with enthusiasm.

Here, then, is Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G Minor, with Martha Argerich at the piano.

In October 1932, Ravel suffered a blow to the head in a taxi accident. The injury was not thought serious at the time, but it’s since been thought that it may have exacerbated an existing cerebral condition.

As early as 1927, a year before he wrote Bolero, close friends had been concerned at Ravel's growing absent-mindedness, and within a year of the accident he started to experience symptoms suggesting a stroke. The exact nature of his illness is unknown.

The remainder of his life was plagued by a malfunction of the brain some say was caused by Pick's disease, a rare form of progressive dementia which increasingly affected his speech and movement. In 1937, he began to suffer pain, had an operation but soon lapsed into a coma.

He died on 28th December, at the age of 62. On 30th December 1937, Ravel was buried in Paris next to his parents. Ravel was an atheist and there was no religious ceremony. He once wrote to a friend:

I have failed in my life. I am not one of the great composers. All the great composers have produced enormously. There is everything in their work; the best and the worst, but there is always quantity. But I have written relatively very little... I did my work slowly, drop by drop.

He may not have thought so, but I think he was a genius.

Before we finish, let’s have a couple of small encore pieces, both solo works written in 1913, the first “in the manner of Borodin” and the second “in the manner of Chabrier”.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Maurice Ravel playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.