Neoclassicism

When I was preparing a programme of The Rite of Spring I had in mind to follow it up with one on Stravinsky after The Rite of Spring. But as I worked on this follow-up I found myself side-tracked by the kind of music Stravinsky was composing in this period, and thought I would instead take this music, Neoclassicism, as the theme.

Stravinsky wrote The Rite of Spring in 1913. Stravinsky was 31 when he wrote the music for which he is best known but he died in 1971 at the age of 88, and he was active as a composer throughout his adult life.

The Rite of Spring ensured that Stravinsky was very well known, notorious even, and people thought they knew what to expect from him: avant garde, perhaps even outrageous music that pushed boundaries of what was acceptable.

However, just a few years after The Rite of Spring was premiered he caused another sensation by abandoning all that had made him famous and turning to Neoclassicism.

With his company, the Ballets Russes, on tour in the United States, the impressario Sergei Diaghilev spent November 1916 browsing through old music in Italian libraries with choreographer Léonide Massine. When Massine suggested doing a ballet on the Pulcinella stories from the Italian commedia dell’arte tradition, Diaghilev agreed, and the two selected some pieces they believed were composed by an Italian called Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. As it happens, they were actually written by a number of other composers of that era. Diaghilev originally wanted Manuel de Falla to orchestrate the music, but this fell through, and Igor Stravinsky was given the commission.

According to Stravinsky, Diaghilev expected nothing more than a “stylish orchestration”. The score Stravinsky presented, however, was for a small orchestra and a trio of singers, and it was not so much stylish as stylized.

This was far more than Diaghilev had expected from Stravinsky, who recalled: “Diaghilev hadn’t even considered the possibility of such a thing. A stylish orchestration was what Diaghilev wanted, and nothing more, and my music so shocked him that he went about for a long time with a look that suggested The Offended Eighteenth Century. In fact, however, the remarkable thing about Pulcinella is not how much but how little has been added or changed.”

The changes Stravinsky made were significant but not fundamental, with few major structural alterations. Stravinsky’s real mark was in his idiosyncratic orchestration. It’s not something you may be aware of at the start of the suite.

At the beginning, there is little hint that his is anything but a straightforward orchestration of an 18th century piece. As the music progresses, hints of Stravinsky begin to appear and towards the end his hand is blindingly obvious.

The Pulcinella Suite, derived from the ballet, was written in 1922, two years after the ballet opened, and was premiered that year in Boston.

Let’s now hear all eight movements of the Pulcinella Suite.

Constant Lambert summed up that piece neatly. He said that Stravinsky was “like a child delighted with a book of eighteenth-century engravings, yet not so impressed that it has any twinges of conscience about reddening the noses or adding moustaches and beards in thick black pencil”.

It marked the end of Stravinsky’s “Russian” period. He referred to it as “my discovery of the past, the epiphany through which the whole of my late work became possible. It was a backward look, of course — the first of many love affairs in that direction— but it was a look in the mirror, too.”

The Neoclassicism created in Pulcinella proved to be one of the most important artistic movements of the 20th century. It was a very deliberate reaction to the Romantic era, order, balance, clarity, economy and emotional restraint were the order of the day.

Think about it: not many great Romantic composers employed emotional restraint.

After Pulcinella came a flood of Neoclassical music, including what you will hear next.

Francois Couperin was a French Baroque composer and the inspiration for the next music you will hear. In the course of his long career Richard Strauss came to be known for forever adapting and changing styles and genres. For a while, he took to Neoclassicism in a big way.

In 1923 he wrote a Dance Suite from Keyboard Pieces by Francois Couperin. Couperin wrote the original music for solo harpsichord in the first quarter of the 18th century. This suite is as different from a great deal of Richard Strauss’s work as, say, Pulcinella is from much of what Stravinsky wrote before that.

Let’s listen to the seventh of the Couperin Suite’s eight movements.

That was from a recording from the 1960s by the Staatskapelle Dresden conducted by Rudolph Kempe.

I’d now like to play some Neoclassical music by Francis Poulenc. He wrote a suite called French Suite After Claude Gervaise in 1930, and it was inspired by a collection of dances by Gervaise, a Renaissance composer.

First, you will hear the second movement, a quite solemn pavane. Then comes a piece Poulenc called a petit marche militaire, and after that a gentle Sicilienne. The pianist here is Andre Previn.

An Italian composer who was very much into Neoclassicism was Alfredo Casella, who did much to resurrect Vivaldi’s work.

In 1926 he wrote a piece for piano and orchestra called Scarlattiana, a kind of fantasia on themes of keyboard sonatas by the 18th century composer Domenico Scarlatti. It’s in five movements, and this is the finale. I think it’s typical of a lot of today’s music. It’s very much a piece of 20th century Baroque.

Three of this work’s five movements, including this one, are fast, witty, rhythmical and, I think you will find, occasionally reminiscent of what we heard earlier by Stravinsky.

The programme so far has been about what is referred to as Neoclassical music. Indeed, the composers themselves were happy to call it such.

The term was first applied in the 19th century to the painting and sculpture of the 18th century that had modelled itself, more or less loosely, on the 'classical' art of ancient Greece and Rome by way of the Renaissance.

In music, though, Neoclassicism was born with Stravinsky, or so Stravinsky himself said. But before Pulcinella there was no shortage of works that offered a contemporary take on music from Baroque or Classical eras. This music is often described as being precursors to Neoclassicism, although much of it sounds as Neoclassical as anything written by Stravinsky.

So in this half of the programme we will focus on some of these so-called precursors to Neoclassicism, beginning with this.

That was the third movement of Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1, which he completed in 1917 and premiered in what was then called Petrograd the following year. The symphony was written in a loose imitation of the style of Haydn, and to a lesser extent Mozart. However, because of this harking back to the past it’s commonly known as Prokofiev’s Classical Symphony. As it happens, Prokofiev described his classical symphony as a “passing phase” whereas he considered Stravinsky’s Neoclassicism as “the base line of his music”.

At around this time many other composers were writing Neoclassical music before its time, if you get my drift.

Ravel would probably have disliked being called a Neoclassical writer, just as he didn’t like being called an Impressionist one. He liked to experiment with musical form but he was also interested in what he called “traditional forms and in the French past”.

Ravel saw the horrors of the Western Front during the First World War at first hand. In 1917, he completed his Le Tombeau de Couperin, as dance suite based on Baroque forms. Tombeau means tomb but in terms of this suite it should be taken as meaning homage – a homage to the 18th century composer Francois Couperin. I’ve used music from this suite before and, as I’ve said before, Ravel dedicated each movement of the suite to the memory of someone he knew who had been killed in the war.

Here, Bertrand Chamanyou is playing the fifth movement, a very simple menuet dedicated to Jean Dreyfus, the half-brother of a very close friend.

I really don’t know why Neoclassicism is commonly said to have begun with Pulcinella. Probably the best example of music that explains my difficulty is Ottorino Respighi’s Ancient Airs and Dances, part of which was written a few years before Stravinsky’s Pulcinella.

In addition to being a renowned composer and conductor, Respighi was also a notable musicologist. His interest in Italian music of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries led him to compose works inspired by the music of these periods.

Ancient Airs and Dances is a set of three orchestral suites, freely transcribed from original pieces for lute. The first of these suites was completed in 1917 and is made up of four pieces. The second, which I’ll play now, is based on music by an Italian Renaissance lutenist called Vicenco Galilei, the father of the much more famous Galileo Galilei. By the way, the second suite was written in 1923 and the third in 1932, and so are generally regarded as most definitely Neoclassical works.

Now for some more music based on early Italian music.

Francesco Malipiero, who was born in 1882 in Venice to an aristocratic family. As well as being a composer he was a noted musicologist who made a study of Monteverdi and had a deep interest in old Italian music.

In 1910 he wrote a set of three pieces he called The Ancient Dances, in which he looked to the 18th century for inspiration. This is the second of the three pieces.

We’ve had a few short pieces in this part of the programme so let’s have a longer work now.

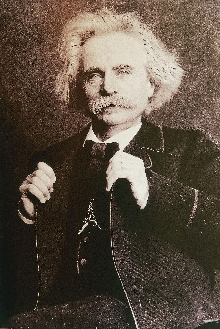

In1884 some music was composed to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the birth of the man said to be the founder of modern Danish and Norwegian literature, Ludvig Holberg.

Edvard Grieg called the work From Holberg’s Time and gave it the sub-title Suite in the Olden Style. He wrote his five-movement Holberg Suite originally for piano and later adapted it for string orchestra. His aim was sidestep the Romantic conventions of the day and instead hark back to the classical era of Ludvig Holberg.

Since Holberg was a contemporary of Bach and Handel, Grieg composed his tribute in the form of a French Baroque period suite. He called the Holberg Suite his “powdered-wig piece”, and you are going to hear all five movements, played by the Academy of St Martin in the Fields conducted by Sir Neville Marriner.

Actually, Grieg originally wrote the Holberg Suite for piano but later adapted it for string orchestra.

Each of the five movements is quite distinct and I thought I would say a few words before each one starts.

So, here’s the first movement, called Praeludium or prelude, played allegro vivace, very fast.

Now an andante piece. It’s a Sarabande, a traditional Baroque dance. The dance originated in, and was very popular in, the Spanish colonies of Mexico, Panama and Guatemala in the 16th and 17th centuries and was brought back to Spain and then on to Italy and France. This movement contrasts nicely with the first movement. It has a more peaceful, thoughtful mood.

Next comes a Gavotte, originally a French country dance which became popular in the French court in Baroque times. It’s a perky, almost aristocratic dance.

I think the fourth movement, an Air, is one of Grieg’s most sublime. He marked the score Andante religioso, meaning play in a relatively slow, devotional manner, as if it were a religious piece.

The final movement is a Rigaudon, which originated in 17th century France as a spritely dance for couples. This movement echoes the liveliness of the prelude features the imagined sounds of a country fiddle player.

We will close with one more brief piece. I once did a programme which looked at how some composers viewed or used the work of other composers. I explained in it that in 1909, the editor of a music journal commissioned six composers to write pieces to mark the centenary of Haydn’s death. You heard three of the six pieces, each one played by Ivana Gavric.

One was a fugue by Charles-Marie Widor one a minuet by Ravel and the third a Hommage to Haydn by Debussy. Well, as these are all Neoclassical works I thought I would finish with another of the pieces that made up this commission. This was by Reynaldo Hahn, a Venezuelan but naturalised French composer.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Neoclassicism playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.