Musical Oddities

In choosing the music for this programme, I haven’t gone for the very odd. So there’s no place here for Stockhausen’s Helicopter String Quartet, which requires the sound of four helicopters. The Italian composer Luciano Berio included in one of his pieces a part that used car springs. I’m not featuring that. Malcolm Arnold wrote a piece for three vacuum cleaners, a floor polisher and four rifles – you’re not going to hear that either. And I’m not going to play John Cage’s Four minutes 33 seconds, because I couldn’t find a recording I liked (that’s a joke, by the way).

Instead of the completely wacky, I’ve chosen what I might call the quite odd. And most of the music you’ll hear this morning is by big-name composers.

I thought I would intersperse the music with some off facts, unrelated to any music you are going to hear. For example, can you guess what links Schubert, Schumann, Delius, Glinka and Scott Joplin? They all had syphilis. There are those who think that Beethoven, Mozart and Smetena did too, by the way.

So let’s get things going with some music.

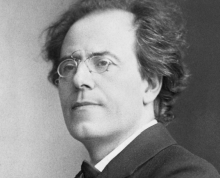

We all have favourite singers, or composers, or pieces of music. We may have favourite symphonies, but what about favourite 1st symphonies? It’s a subjective matter, of course, but I can tell you what mine is. It’s Mahler’s 1st, completed in 1888 when he was 28.

It begins very quietly, with a kind of ethereal shimmer by the strings, and ends with thunderous drama. I find the whole symphony breath-taking and original.

For the premiere, in Budapest in 1889, Mahler told people that his music was loosely based on a novel called The Titan by a popular writer, Jean Paul. After the premiere, Mahler started revising his symphony, and he eventually decided to drop the association with Jean Paul's book.

But the name of the symphony, "The Titan," stuck.

So, what’s odd about it? Well, the first three performances of Mahler’s first symphony contained five movements, including a serenade-like second movement titled Blumine. Subsequent performances left it out.

The Blumine movement was originally part of some incidental music composed by Mahler in two days in 1884, for a performance of a play by Joseph Victor von Scheffel.

The Blumine movement in the symphony contains little or no revisions from the original version. Mahler had become infatuated with an attractive blonde soprano called Johanna Richter. It’s thought that she was his inspiration for the movement.

However, Mahler expressed contradictory opinions about the movement. In a letter about the completion of the incidental music, he wrote: "I completed this opus in two days, and I must tell you that I am very pleased with it." Later, though, he stated that found it too sentimental and became annoyed with it.

For all that, he liked it enough to include it as a movement in his first symphony, but he removed it completely from the work after the symphony’s third performance.

Mahler stated that the main reason he removed it was "because of too strong a similarity of the keys in neighbouring movements". This is confusing, bearing in mind that the Blumine is in C major, a key that none of the other movements remain in significantly.

Perhaps the real reason that may have led Mahler to discard the Blumine movement from his symphony is the negative response to it. In a review of the 1st symphony’s third performance one critic dismissed the movement as "trivial".

Whatever Mahler’s reasoning behind the removal of Blumine, his decision has been met with general approval. As one of Mahler’s biographers wrote: "There can be no doubt as to the authorship of ‘Blumine,’ and yet few other arguments can be stated in its favour. It is the music of a late-nineteenth-century Mendelssohn, pretty, charming, lightweight, urbane, and repetitious … just what Mahler’s music never is."

The Blumine movement remained unplayed until it was rediscovered by another biographer in 1966.

A year after later, Benjamin Britten gave the movement’s 20th-century premiere at the Aldeburgh Festival, the first time the music had been heard since 1894. Since its discovery and publication, Blumine has been performed in different concert formats; for example, as a stand-alone work isolated from the symphony; or before or after a performance of the four-movement symphony.

However, many notable conductors have chosen to ignore the Blumine movement in performances of Mahler’s 1st.

I have my own thoughts about whether or not the 1st Symphony would be better with the Blumine included – I think most definitely that it would not. However, let’s hear it performed by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra conducted by Michael Tilson Thomas.

The next piece you are going to hear was composed 297 years before that movement’s premiere. You are going to hear ‘My Lord Chamberlain, His Galliard’, by John Dowland, who could probably be more accurately described as a Renaissance composer rather than a Baroque one.

It’s not certain where Dowland was born: some think London, some Dublin. He was a musician in both the Danish court and the court of King James I (or, as this is Scotland, King James VI).

This piece is an oddity in that it’s a lute duet – that is, for two players. But for only one lute.

One player must sit on the other’s lap and occasionally take over. It’s said that the work "allows the possibility of an intimate embrace".

Here’s another fact for you. I told you earlier about the composers who had syphilis. Well, did you know that Stravinsky, von Weber, Boccherini, Purcell, Paganini and Chopin all had TB?

Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber, who lived from 1644 to 1704, was a composer and violinist in Salzburg.

He was generally considered to be the greatest violin virtuoso of his time and the composer of demanding and revolutionary music for solo violin and for the orchestra.

Let’s hear a short piece by him, just to show you the sort of thing he was writing. It’s called simply L’Aria and it’s played by Christina Pluhar, an expert in Baroque instruments.

Having heard that von Biber could write a nice tune, let’s now get round to his oddity.

In 1673 von Biber created his Battalia, a set of movements for string orchestra which describe battles.

In the second movement, Biber mixes a number of folk songs, combining of several melodies simultaneously that don’t fit together. You are going to hear eight different parts played simultaneously and in different keys – seven in all – to create the impression of a battle.

Listen to this noise and remember that Biber has been described as one of the finest violinist of the 17th century, one of the first great instrumental composers and a thoroughly idiosyncratic musical thinker. This piece certainly illustrates that last point. Thankfully, it lasts only 47 seconds.

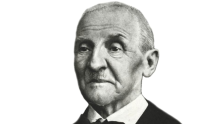

I’ve never used anything by Anton Bruckner in any of my programmes, and I don’t know why. Some of his music is highly original, beautiful, serene and often spiritual. And his symphonies are inclined to be monumental.

That said, the guy was something of an odd-ball. He’s been described as a country bumpkin with an unhealthy interest in dead bodies and teenage girls. He was a cranky, obsessive weirdo yet he wrote some of the 19th century's grandest and most ambitious symphonies.

You are about to hear the third movement of one of those symphonies.

Bruckner wrote this D minor symphony in 1869, between his 1st and 2nd symphony. It was originally called Symphony No. 2, while his C major symphony of 1872 was called No. 3.

Throughout his life, Bruckner lacked self-confidence and was particularly sensitive to criticism. He was said to be devastated when the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra’s principal conductor at the time, Otto Dessoff, said of this symphony, “But where is the main theme?”

In 1895, when Bruckner reviewed his symphonies so that he could have them published, he declared that this symphony "does not count".

He wrote on the front page "nullified” and replaced the original "Nr. 2" with a symbol which was later interpreted as the numeral zero and the symphony got the nickname Die Nullte ("No. 0").

The work, then, is sometimes referred to as "Symphony in D minor, opus posthumous", but is in English most often called "Symphony No. 0". It was premiered in 1924.

This, then, is the third movement of Bruckner’s Symphony No. 0, with Sir Georg Solti conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Now for our last set of pieces before the break, and for a story I found fascinating. Hands up if you have heard of a Baroque composer called James Oswald.

I knew nothing about him until recently, and I think it’s curious that he’s not well known, at least in this part of Fife.

James Oswald was born just 15 miles from here, in Crail, in 1710. His father was the village drummer – a kind of town crier who would bang out announcements in the village and around its fish market. It gave him an annual salary of £10 and several pairs of shoes – enough to get by on.

James was raised on a diet of fish – and traditional folk tunes. He soon began writing folk-style melodies, playing them on the fiddle and 21. When he was 21 he left the family and moved to my home town, Dunfermline, to earn his living as a music teacher and dancing master.

He spent much of his time on the country-house circuit, teaching wealthy families the latest steps and giving after-dinner recitals of songs and minuets in the Italian style, along with his variations of Scots tunes.

Four years later, the ambitious James moved to Edinburgh, where he continued to teach and compose. He also discovered that he had a talent for publishing music. He was keen to show the public that he could not only write and publish music in the Scottish style, but he could also adapt to trends from the Continent.

His Sonata on Scots Tunes became hugely popular. After six years in Edinburgh he was lured by the bright lights of London, where he opened his own publishing shop and began to make serious money from his compositions, which he adapted quickly to suit London tastes. He offered Londoners lessons in Scots music.

Oswald, then, had made himself into a professional Scotsman, composing, performing and publishing Scots-inspired work. Oddly, though, he became particularly well-known for his compositions for an instrument he couldn’t play, the English guitar, a round wire-strung forerunner of today’s guitar. He wrote a great many pieces for it. Oswald was now mixing with the English upper classes, making friends with people such as John Robertson Lytton, the owner of Knebworth House in Hertfordshire.

And he worked his way into the royal circle, and in 1761 he became official chamber composer to King George 111.

Oswald’s talent as a composer was as a miniaturist with a flair for melody, and this is best seen in his collection of 96 sonatas called Airs for the Seasons. There were Airs for the Spring, for the Summer, and so on, and with an eye to the commercial market he ensured that each suite could be accommodated on one sheet of paper. Most were written for the violin, cello and harpsichord.

So, Oswald was a real rags-to-riches story. He was also quite successful in his private life. He was widowed and left with a family but when his friend John Robertson Lytton died he married his widow Leonora, which meant that he spent the rest of his days – and died in – Knebworth House.

Let’s hear a couple more of his pieces, both of which are in what he called Italian style. This is the second movement of his Serenata No. 5

Now here’s one of his guitar pieces, Divertimento No. 4

Oswald quickly became a name on the London music scene in the 1740s and 50s, and it helped that he had a good business sense. His compositions were mostly market driven - French, Italian, English and French style, whatever he could sell, he would write.

He also produced endless volumes of a very comprehensive book, his Caledonian Pocket Companion, which was hugely in demand and packed full of more than 550 playable and accessible arrangements of traditional tunes.

The next piece you are going to hear is a tune called Rory Dall’s Port.

Did you recognise that tune? Robert Burns borrowed it for one of his best-known songs, Ae Fond Kiss. I know this is supposed to be a forum for classical music but I thought I’d finish the session before the break with a rendition of Ae Fond Kiss.

It’s a song that has been recorded by countless artists, including a striking violin rendition by Nicola Benedetti, but I chose the Scottish traditional singer Sheena Wellington, who memorably sang at the Scottish Parliament’s opening ceremony in 1999. Sheena comes from Dundee, which as it happen is almost exactly the same distance from Ceres as is Crail, James Oswald’s birthplace.

It’s time now for Mozart. That would be a good thing, no? Well perhaps not.

In fact, I am not going to play the next piece I have programmed if someone would prefer that I don’t. You see, it’s very rude. It’s in German, but such is the nature of German you would have no doubt as to what’s being sung.

It’s a two-minute song but if anyone would prefer that I don’t play a very bawdy piece by Mozart with German swear words, I’ll move skip it and move on to the next piece.

Mozart may have written some of the most beautiful and profound music ever written but he was also extremely foul-mouthed and particularly fond of particularly crude humour. His letters are littered with four-letter words, or their German equivalent, and his jokes were frankly infantile.

Mozart wrote the short song you are about to hear in 1782. He died in 1791 and his widow, Constanze, sent the manuscripts of it and some other rather rude songs to publishers eight years later, saying they would need to be adapted for publication.

The publishers changes the title and lyrics of this canon to the more acceptable ‘Let us be glad’.

It has been suggested, by the way, that Mozart may have had Tourette’s Syndrome, which can lead to people swearing quite freely.

In Mozart’s defence, it should be said that humour using rude words or about bodily functions was particularly prevalent in Europe in Mozart’s time, and songs like this wouldn’t have raised eyebrows quite as much as they do today.

My apologies to anyone here with sensitive sensibilities. And, mas I say, I don’t think you need to be able to understand German to get the gist of this.

@[Mozart - "Leck mich im Arsch" - Canon in B flat for 6 Voices, K. 231 / K. 382c(https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C78HBp-Youk)

I take it I don’t need to translate the words.

According to theatre director Peter Hall, Margaret Thatcher refused to believe Mozart had such a foul mouth.

He explained, “She gave me a severe wigging for putting on a play that depicted Mozart as a scatological imp with a love of four-letter words. It was inconceivable, she said, that a man who wrote such exquisite and elegant music could be so foul mouthed. I offered (and sent) a copy of Mozart’s letters to Number Ten the next day; I was even thanked by the appropriate Private Secretary. But it was useless: the Prime Minister said I was wrong, so wrong I was.”

Having heard some Mozart I thought it would be an idea to play some Beethoven. The first Boogie Woogie hit was something called Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie, recorded by someone called Jimmy Blythe and released in 1929. Here are just a few bars from that piece performed by the gloriously named Pinetop Perkins.

And now the Beethoven. He wrote his Piano Sonata No. 32 in 1823. It was the last of his piano sonatas – he died four years later. And I think he gave Jimmy Blythe an idea 106 years later. We don’t have time to hear the whole sonata, but we can hear a minute or so, which comes midway through the second movement. Beethoven, as you will hear, was clearly an innovator.

The pianist here is Maurizio Pollini.

Now that was an oddity.

Most of my odd facts so far have related to death, so here are some more.

Mike asked me at the last session how Alexander Scriabin died. Well, he died of a shaving cut. He nicked his upper lip and a few days later saw that the cut had developed into a pimple. Five days later he was bed-ridden with blood-poisoning and died just a couple of weeks after his last shave.

Purcell died aged just 36 after he caught a chill when his wife locked him out when he returned late from a tavern.

Alexander Borodin dropped dead in full national dress on the dance floor at a ball in St Petersburg.

The Austrian composer Anton Webern was shot dead in 1945 by a US Army cook while he was having a smoke. The soldier, by the way, was full or remorse and killed himself 10 years later.

Another Austrian composer, Alban Berg, met his maker after being stung by a bee on the back. A carbuncle formed and his wife attempted a home operation using a pair of scissors. Blood poisoning and death followed.

OK, some more music now.

I find it very odd that a bullet fired by a Russian soldier during the First World War should have been responsible for several excellent, though in their way slightly odd, pieces of classical music.

Paul Wittgenstein was the older brother of the famous philosopher Ludwig. In fact, he had 10 siblings, three of whom – all brothers – committed suicide.

Born in Vienna, Paul was an extremely gifted pianist who was brought up in a household that was frequently visited by the likes of Brahms, Mahler and Richard Strauss.

His family was stinking rich. Wittgenstein’s father made a fortune in the iron and steel industry, and became one of Europe’s wealthiest men. As a result, he was well connected among Europe’s rich and famous, including the top musicians of the day.

Paul Wittgenstein made his public debut to favourable reviews in 1913 but a year later the First World War broke out and he was called up by the Austrian army to serve on the eastern front.

In 1914, in his first week on the front, he went on a reconnaissance mission somewhere in the Ukraine, he was shot in the right elbow by a Russian sniper bullet.

He was captured by the Russians, taken to a field hospital and had his lower right arm amputated. He was then sent to a prisoner-of-war camp in Omsk in Siberia where he had a second amputation, this time just below the shoulder.

It would have been a devastating blow for any young musician. Through the Danish ambassador, he wrote to his old teacher, Josef Labor, who incidentally was blind, asking him to write a concerto for the left hand. Labor soon replied, saying he had started work on a piece for his former pupil.

Wittgenstein was released in December 1916 as a result of an exchange of wounded soldiers facilitated by the Pope.

When the war ended and he returned home, he began to study pieces written for the left hand, learning Labor’s new piece and performing it in public.

Piano pieces for the left hand weren’t all that unusual. At the time, it’s reckoned that there were around 270 such compositions.

Anyway, Wittgenstein approached famous composers including Prokofiev, Ravel, Britten, Korngold, Richard Strauss and Hindemith asking them to write music for him to perform.

They all did, but although Ravel’s concerto is perhaps the better known, Prokofiev’s has also stood the test of time.

Wittgenstein was notoriously obstreperous. He initially bridled at aspects of Ravel’s concerto and also complained that the two compositions written for him by Richard Strauss were disproportionate and unnecessarily modern.

There are varying stories about his attitudes to Prokofiev’s Left Hand Concerto, which is generally called simply his Concerto No. 4. Some say that he steadfastly refused to even attempt to perform it. Others say that he was simply not prepared to play it until he felt he could fully appreciate it. He is said to have written that he did not understand a single note of it.

Whatever the reason, Wittgenstein never got round to playing it, although he and Prokofiev always remained on friendly terms.

It was the only one of Prokofiev's complete piano concertos was never performed in his lifetime. There is, of course, a story about the premiere, which took place in Berlin in 1956, three years after Prokofiev died and a quarter of a century after he wrote it.

During World War Two, a German pianist called Siegfried Rapp lost his right arm in remarkably similar circumstances to Wittgenstein, while servicing on the Eastern Front. His injury, however, was called by shrapnel rather than a bullet.

Around 1950, Rapp asked Wittgenstein for permission to perform the work, which has languished unheard since it was written. himself. Wittgenstein refused in no uncertain terms.

He wrote to him in June 1950: “You don't build a house just so that someone else can live in it. I commissioned and paid for the works, the whole idea was mine ... But those works to which I still have the exclusive performance rights are to remain mine as long as I still perform in public; that's only right and fair. Once I am dead or no longer give concerts, then the works will be available to everyone because I have no wish for them to gather dust in libraries to the detriment of the composer.

However, Wittgenstein relented and the work was premiered in Berlin in September 1956.

You are going to hear all four movements, with Seigi Ozawa, who has two hands, playing with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Leon Fleisher.

I’d now like you to hear a piece you will know. But I think it’s something of an oddity that you probably don’t know the composer.

Does the name Remo Giazotto mean anything to you? It should, for he wrote one of the best-known Baroque pieces – and he did so after the Second World War.

What happened this – or so Giazotto claimed. He claimed that shortly after the war he obtained from the State Library in bombed-out Dresden a fragment of a manuscript from a slow second movement of an otherwise unknown trio sonata by the Venetian Tomaso Albinoni, who was born in 1671. This fragment featured the bass line and just six bars of melody.

Giazotto was a musicologist from Milan and in 1945 he set out to write a biography of Albinoni. However, he had much greater success with the music you are about to hear.

He said he had completed Albinoni’s single movement in tribute to the composer, and he published it in 1958 under his own name with the title Adagio in G Minor for Strings and Organ on Two Thematic Ideas and on a Figured Bass by Tomaso Albinoni.

It’s not known whether he wrote the Adagio for a laugh, to try and make a few lira, or because he was trying to prove a point. But it’s likely that if he’d published the piece as a work written in the Italian baroque style by himself alone, without Albinoni’s name attached, it would have died without a trace. To this day, Albinoni’s fragment has not been produced and no official record of its presence has been found in the collection of the Saxon State Library. However, Giazotto’s work is now extremely popular and well known.

Giazotto died in 1998 and as well as writing a well-respected book about Albinoni he wrote a comprehensive biography of Vivaldi.

Here, Sir Neville Marriner is conducting the Academy of St Martin in the Fields.

Before we finish, I would now like you to hear two piano pieces that really aren’t odd at all.

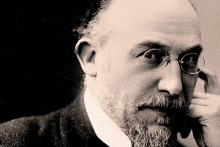

The reason I’m featuring them is that they give me an excuse to tell you something about the biggest oddity in today’s programme – the French composer Erik Satie.

To say Satie was an eccentric would be an understatement. He gave many of his compositions ridiculous names like Veritable Flabby Preludes for a Dog, Sketches and Exasperations of a Big Book Made of Wood and Waltz of the Chocolate with Almonds.

He also like to give odd instructions to performers. He marked one of his piano pieces: “To be played with both hands in the pocket.”

Another thing: he would eat only white food: eggs, sugar, some fish, coconuts, some cheese and so on.

And he was very strict about his daily timetable. Here’s a passage from his memoirs.

“An artist must organise his life. Here is an exact timetable of my daily activities.\ I rise at 7.18, and inspired from 10.23 to 11.47. I lunch at 12.11 and leave the table at 12.14. A healthy ride on horseback round my domain follows from 1.19pm to 2.43pm. Another bout of inspiration from 3.12 to 4.07pm. From 4.27 to 6.47pm various occupations (fencing, reflection, immobility, visits, contemplation, dexterity, swimming, etc). Dinner is served at 7.16 and finished at 7.20pm.”

And so it goes on.

“I sleep with only one eye closed, very deeply. My bed is round, with a hole to put my head through. Once every hour a servant takes my temperature.”

Here, then are two short pieces by Erik Satie, the well-known Gnossienne No. 1 and then Le Piccadilly, both played by French pianist Alexandre Tharaud.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Musical Oddities playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.