Scotland in Literature

I’m not saying this because I am Scottish but the number of musical works based on literature from or about Scotland is truly amazing.

I think it reflects the tremendous appetite that existed throughout Great Britain and the Continent, particularly during the Romantic period, for all things Scottish. The perceived romance of its violent wars and feuds, as well as its folklore and mythology, intrigued 19th century readers and audiences.

The works of Robert Burns undoubtedly lent themselves to musical interpretation, and in Sir Walter Scott Scotland had the premiere Romantic writer of the day. Burns and Scott both feature in this programme, but it’s not just about them, as you will hear.

One of the things I have tried to do is, where possible, to find a local link to the poems, plays and novels that inspired the music you are about to hear.

Let’s begin with what I suppose is a pretty weak example.

Max Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy is one of the most popular works in the classical repertoire.

Completed in 1880, it’s a composition for violin and orchestra in four movements based on Scottish folk melodies. You are going to hear the fourth movement, an arrangement of a tune to which Robert Burns provided lyrics for Scots Wha Hae, which for many years was regarded as an official national anthem of Scotland until it was supplanted by Scotland the Brave and Flower of Scotland.

This medieval marching tune, Hey Tuttie Tatie, is said to have been played by the army of Robert the Bruce before the Battle of Bannockburn, so there’s a very tenuous link with my home village of Ceres.

You will know that the monument in the centre of Ceres commemorates the facts that so many men from the village fought with Bruce at Bannockburn, and so Bruch’s music, written 560 years later, has an echo of what these Ceres men will have heard.

This is the violinist Itzhak Perlman and the New Philharmonia Orchestra playing the fourth movement of Bruch’s Scottish Fantasy.

If you drive from Ceres to the East Neuk of Fife, as you go downhill towards the coast, you may well see the Bass Rock and Berwick Law. Behind them, in the distance, are the Lammermuir Hills, and they provided the setting for Gaetano Donizetti’s opera Lucia di Lammermoor, a tragic opera in three acts based on Sir Walter Scott’s novel The Bride of Lammermuir, written in 1819.

The opera was written in 1835 but is set in the 17th century. The story concerns the emotionally fragile Lucy Ashton (Lucia) who is caught in a feud between her own family and that of the Ravenswoods.

You are going to hear Joan Sutherland singing an aria from the third act, ‘Spargi d’amore pianto’, ‘Sprinkle with bitter tears my earthly remains’.

Next comes another piece inspired by Sir Walter Scott – and it won’t be the last today.

Marmion: A Tale of Flodden Field, published in 1808, is a historical romance in verse set in 16th century Britain, and ending with the Battle of Flodden in 1513. It was Scott’s second major work, and his publisher offered him 1,000 guineas for its copyright before he had read a word. Waverley, incidentally, was his first major work, and it quickly became the most successful novel ever published in English.

In 1864, Arthur Sullivan was commissioned by the Philharmonic Society of London to write an overture based on Marmion, which concerns a fictitious rogue nobleman at the court of King Henry VIII, who after various acts of treachery finally meets his end at Flodden.

By the way, I started to read Marmion but had to give up after all of 20 seconds.

However, I do know that it contains one Fife reference: “Yonder the shores of Fife I saw, Here Preston Bay and Berwick Law. The gallant Frith the eye might note, Whose islands on its bosom float, Like emeralds chased in gold.”

And ‘Emeralds Chased in Gold’ happens to be the title of a book, written by John Dickson on 1899, on the islands of the Forth.

Here the overture Marmion by Sir Arthur Sullivan is played by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, under Royston Nash.

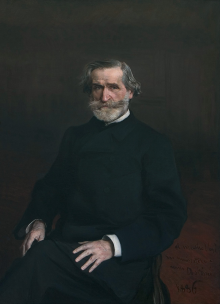

I know that Macbeth isn’t a Scottish work but thespians do call it The Scottish Play because they fear saying the play’s name will bring a theatre bad luck. On that basis, I’ve chosen something from Macbeth, Giuseppe Verdi’s 10th opera and the first Shakespearean work he adapted for the stage. Verdi wrote Macbeth in 1847 and 18 years later he revised it for a production in Paris. Incidentally, Verdi spoke very little English and read Shakespeare in Italian. He only saw the play in the same year his opera was premiered. By the time he revised his opera he had seen it many times.

You are going to hear Anna Netrebko singing an aria as Lady Macbeth from the first act of that Paris production, Vieni! t’affretta! (Come on, Hurry Up!).

Verdi didn’t want the soprano playing Lady Macbeth to make a particularly beautiful sound. He wanted her to sing with a tone that could be ‘hard, stifled, and dark’ with ‘something devilish’ in her voice.

Here, Lady Macbeth has just read out loud a letter from Macbeth saying that he has been appointed Thane of Cawdor and a group of witches prophesied that he would soon be both Thane and King of Scotland. Lady Macbeth is excited about this prospect and sings of her delight that her husband will soon be King. All this scheming woman’s ambitions were coming true.

She sings:

Macbeth, you are an ambitious man

You want to be great, but will you be wicked?

The way to power is full of crimes

And plague on him that begins that way doubting and then goes back.

Come on! Hurry up!

I will fire your cold heart!

I will make you able to

complete the bold undertaking.

The witches promise you the Scottish throne

What are you waiting for? Accept this gift! Ascend it and reign!

This is Anna Netrebko.

Is there a Fife connection to the MacBeth story? Of course there is. The Thane of Fife – a thane is an old Scots equivalent to a duke – was Macduff, who kills Macbeth in the final act of the play. The clan Macduff was the most powerful family in Fife in the Middle Ages, and Macduff’s stronghold was his castle, now in ruins, next to the cemetery in East Wemyss, near Kirkcaldy and just 12 miles from my home in Ceres. MacDuff, then was a Fifer.

Here’s another aria from Verdi’s opera. Macbeth has killed Macduff’s children and wife and Macduff is stricken by grief. He sings ‘O figli, o figli miei!

Ah, sons, my dear sons!

You all were killed by that tyrant,

and, together with you, your unhappy mother too!

Ah! I let into the claws of that tiger

the mother and her sons!\

Here, Luciano Pavarotti is singing the role of Macduff, Thane of Fife, though sadly without the Kirkcaldy accent he really should have.

Perth is just 29 miles from where we are today, and The Fair Maid of Perth (or St Valentine’s Day) is the title of another of Scott’s works, a novel published in 1828.

The book is inspired by the strange but true story of the somewhat staged Battle of North Inch in Perth, where my wife and I were walking a few days ago. It was fought between two clans, the Chattans and the Kays, in 1396.

To minimise deaths, it was decided that just 30 men be picked to represent each side, and the battle – which was witnessed by King Richard 11 – was won by the Chattans, who killed all but one of their opponents, at the cost of 19 deaths on their side.

There is a Fife reference: the book does feature the castle – not the Palace – of Falkland.

La Jolie Fille de Perth is a four-act opera by George Bizet based extremely loosely on Scott’s novel. It was premiered in Paris in 1867.

The opera itself is full of attractive and often inspired music but it’s generally acknowledged that it was let down by a pretty ropey libretto.

Here, Sir Thomas Beecham is conducting the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in the Bohemian Dance from Act 11.

There are three strands to the next story which will come together with what I don’t think I will call music.

Matyas Seiber was born in Budapest in 1905 but lived and worked in the UK from the age of 20. He output was extremely diverse, with some of his music reflecting Bartok and Kodaly, although he also produced jazz, film scores and lighter music.

And it’s to his lighter music that we’re going now.

If, in December 1883, you made the 13-mile journey by road from Ceres to Tayport, the chances are you would have been among the many thousands who flocked to that part of the Firth of Tay to see what had become known locally as The Monster, a humpback whale that had first appeared off Dundee on 12th November that year.

The poor animal obviously didn’t realise that at that time Dundee was Scotland’s premier whaling port, and some of the city’s whalers decided to kill it. After a few failed attempts, they finally managed to harpoon it on New Year’s Eve, and it was towed alive to the Firth of Forth.

However, after a struggle it broke free and escaped. A week later, it was found dead and was towed to Stonehaven and beached. A local entrepreneur, John Wood, bought the whale and had it transported to his yard in Dundee. On the first Sunday that it was there, 12,000 people paid to see it.

As a boy, I loved the work of William Topaz MacGonagall. He was and is the most read Scottish poet in the world apart from Robert Burns. He was also without question the worst poet ever to have been published. I found a copy of his works in the school library and loved its awfulness so much that I bought a copy. I wish I still had it.

MacGonagall was born and died in Edinburgh but he is closely associated with Dundee. His most famous work was on the Tay Bridge disaster of 1879, but his poem The Famous Tay Whale takes some beating. Part of it reads…

And my opinion is that God sent the whale in time of need,

No matter what other people may think or what is their creed;

I know fishermen in general are often very poor,

And God in His goodness sent it drive poverty from their door.

So Mr John Wood has bought it for two hundred and twenty-six pound,

And has brought it to Dundee all safe and all sound;

Which measures 40 feet in length from the snout to the tail,

So I advise the people far and near to see it without fail.

In 1958, Matyas Seiber set The Famous Tay Whale to Music for the second Hoffnung Music Festival, a humorous classical music festival held in the Royal Festival Hall in London. His arrangement calls for a narrator, full orchestra, a fog horn and an espresso coffee machine. This is a recording of the premiere, with the great English actress Dame Edith Evans providing the narration. I’m sorry about this but I couldn’t resist it.

Limekilns is a nice village in West Fife on the shores of the Forth between the Forth and Kincardine bridges. It became quite well known as one of the places featured in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Kidnapped. It’s much less well known as the place where George Thomson, whose father was schoolmaster there, was born in 1757.

Thomson had no great musical ability per se but he was something of a Simon Cowell of his day – he knew how to make money from music.

Thomson was a book and music publisher, and in 1792, he hit on the brilliant idea of marrying traditional songs to leading composers of the day. And so he contacted Robert Burns, who was happy to help and submitted no fewer than 114 songs for Thomson’s A Collection of Scottish Airs.

Thomson then set about commissioning new arrangements for these airs, at first going to composers such as Haydn and Weber. Much of the work was carried out despite the constraints imposed by the Napoleonic wars, which meant much of the correspondence between Thomson and his composers had to be smuggled through diplomatic channels or sent in duplicate on circuitous routes via Malta, for example, to ensure that at least one survived the journey.

Overall, he commissioned more than 200 settings from Haydn. But in 1803, seven years after the death of Burns, Haydn became too ill to work. Thomson then approached Beethoven with the idea of creating an unbeatable partnership.

However, relations between the two were prickly from the outset. Almost everything Beethoven wrote, Thomson said, was too complicated for amateur musicians, and that was the very lucrative market Thomson was targeting. And Beethoven didn’t take too kindly to being told to keep his arrangements simple.

Here’s Thomson writing to Beethoven: “I permit myself the liberty to request that the composition of the accompaniment for the piano to be the most simple and easy to play because our young ladies, when singing our national airs, do not like and hardly know how to play a difficulty accompaniment.”

And again: “Tell me, my dear sir, is it not possible for you to demonstrate the enchanting power of your art in a simpler form?”

And yet again: “Permit me to request that you make the piano parts completely simple and easy to read at sight, and easy to play.”

Now here’s Beethoven to Thomson: “I will take care to make the compositions as easy and pleasing as far as I can and as far as is consistent with that elevation and originality of my style.”

And again: “You are dealing with a true artist who likes to be paid honourably but who likes glory and also the glory of art more, and who is never content with himself and tries always to go further and make yet greater progress in his art.”

The letters get increasingly tetchy. Beethoven also complained that Thomson did not send him the songs’ lyrics; only an outline of the story.

He wrote: “I cannot understand how you, who are a connoisseur, cannot realise that I would produce completely different compositions if I had the text to hand, and the songs can never become perfect products if you do not send me the text.”

They also argued about money. Beethoven drove a hard bargain with Thomson, eventually beating him up to a fee of four gold ducats rather than three. In return, he wrote the settings for 125 songs. Accompaniments, Thomson called them; Beethoven called them compositions.

In the end, Thomson broke off the project because, as he preached over the course of 17 years’ of correspondence, the settings were much too much for the young ladies of Scotland. He would get his daughter Annie to try to play Beethoven’s arrangements. If she found them to be difficult, he concluded, so too would his target market.

The songs never became the great hits Thomson was hoping for, and he made not a penny from them. As for Beethoven, they gave him a steady trickle of income but they can’t be regarded as among his greatest achievements.

You are going to hear two of them, sung by the British soprano Sophie Daneman. The Lovely Lass of Inverness, and The Sweetest Lad was Jamie.

By the way, Thomson’s grand-daughter married Charles Dickens.

Let’s change the tone now, and have something orchestral. Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley, which was published anonymously, is often regarded as the first historical novel. It’s about an English soldier, Edward Waverley, and his trials and tribulations while serving in the Hanovarian army during the Jacobite rebellion.

The book became so popular that Scott's later novels were published as being "by the author of Waverley". His series of works on similar themes written during the same period have become collectively known as the ‘Waverley Novels’. And a railway station in Edinburgh was named after them.

Hector Berlioz was an avid reader of Scott’s work and he took Waverley as his inspiration for his overture of the same name, composed just 14 years after the book was published. Waverley was the composer’s official Opus 1.

It’s in two parts – a slow introduction followed by an allegro that has a certain ‘Caledonian’ wildness about it. As he developed as a composer, Berlioz increasingly despaired of Waverley. As well as a composer Berlioz was a noted conductor but he never once conducted this work.

This is Waverley performed by the LSO under Valery Gergiev.

Kirriemuir in Angus is just 34 miles by road from Ceres and is best known as the birthplace of JM Barrie, the author of Peter Pan, the story of a mischievous little boy who can fly and who never grows up.

Barrie first used the character Peter Pan in an adult novel, The Little White Bird, published in 1902. He returned to the character as the centre of his stage play entitled Peter Pan, Or The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up, which premiered in 1904 in London. Barrie later adapted and expanded the play's story line as a novel, published in 1911 as Peter and Wendy.

Ernst Toch is not a name I had come across before researching this programme. He was an Austrian composer of classical music and film scores who died in 1964.

Toch went into exile during the Nazi era, later became a professor at the University of Southern California teaching Music and Philosophy, and received the Pulizer Prize in 1957. Like Matyas Seiber, whose Tay whale music you heard earlier, Seiber attended the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt.

He wrote Peter Pan: A Fairy Tale for Orchestra in 1956 and many have seen echoes of Berlioz, who you just heard, and Mendelssohn in it.

This is the Louisville Orchestra playing the final movement.

Next, Hamish MacCunn’s Land of the Mountain and the Flood, which I chose not to feature in last week’s programme on mountains because I wanted to use it here.

The title of the piece came from Sir Walter Scott’s poem The Lay of the Last Minstrel.

O Caledonia! stern and wild,

Meet nurse for a poetic child!

Land of the heath and shaggy wood,

Land of the mountain and the flood,

Land of my sires!

MacCunn was born in Greenock in 1868 and studied at the Royal College of Music in London, where he later became professor. He composed Land of the Mountain and the Flood at the age of 19.

This 1968 recording is of the Scottish Symphony Orchestra (it became the Royal Scottish Symphony Orchestra in 1977) under Alexander Gibson (he became Sir Alexander Gibson also in 1977).

This music is pure Victoriana in that it offers an unashamedly lyrical, romantic view of the Scottish landscape.

To finish today’s programme, I’ve chosen a piece by Maurice Ravel, his Chanson ecossaise.

He wrote a set based on popular songs, including a Spanish one and an Italian one, and this is his Scottish one.

It’s his take on the Burns song The Banks O’Doon, sometimes called ‘Ye Banks and Braes’. It was written in 1910, a year before Ravel visited Scotland for the first time, but the piece was lost and rediscovered in 1975.

The singer here is the Albanian soprano Inva Mula.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Scotland in Literature playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.