Weddings and Marriage

I wrote this programme to coincide with my wedding anniversary. Before the programme starts properly, though, I thought I would l would introduce a piece whose meaning may or may not seem to you to be relevant.

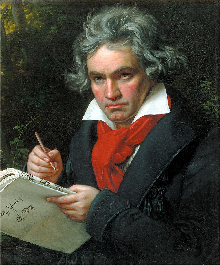

That was Lang Lang playing Beethoven’s Bagatelle No. 25. My wife Lisa’s actual name is Eliza and that piece, as I am sure you will know, is also known as Für Elise. I know, I’m a big softy at heart.

The funny thing is, it may be that the piece should not be called Für Elise. It’s been suggested that the title of the piece may have been transcribed incorrectly and that it was actually called Für Therese. The story is that in 1810 Beethoven asked one of his piano students, Therese Malfatti, to marry him but she completely blew him out for someone called Wilhelm von Drossdik, who was much richer and better dressed than Beethoven. It’s said that Beethoven articulated his sense of rejection and longing in one of the most famous piano works ever.

However, it has also been contended that the piece was written for a German soprano called Elisabeth Rockel, another girl it’s been claimed Beethoven wanted to marry. And just a few years ago another theory emerged: that Elise was a young German soprano called Elise Barensfeld. We may never know.

Anyway, back to our theme. You are at a church wedding. Mendelssohn’s Wedding March strikes up and in glides the bride with her father. You are all eyes and your thoughts and emotions are all over the place. You’re looking at her dress, you’re a bit weepy and your new shoes are hurting. Ladies, you thought your hat was OK in the shop but now you realise it’s a bit OTT. Oh, and you are wondering if the bride is pregnant.

What you are not doing, however, is listening to the music. Here’s your chance to hear the music divorced from the wedding, so to speak. This is Seiji Ozawa conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

That music, of course, comes from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a suite of incidental music to Shakespeare’s play composed by Mendelssohn in 1842. Actually, Mendelssohn wrote a concert overture, Midsummer Night’s Dream, in 1826, when he was just 17, and he incorporated it in the later incidental music. The Wedding March was first used at a wedding ceremony in Tiverton in Devon just five years after it was written. However, it didn’t become popular as a wedding piece until Victoria, The Princes Royal, one of Queen Victoria’s daughters, chose it for her wedding to Prince Frederick William of Prussia in 1858.

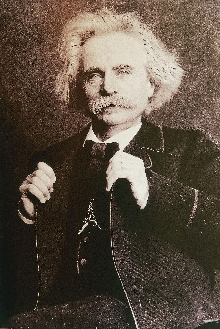

Next comes another piece which the composer wrote with his loved one in mind. In fact, Edvard Greig composed Wedding Day at Troldhaugen in 1896 as a 25th wedding anniversary present for his wife Nina.

The very festive first section of the piece describes congratulations and best wishes that are given by guests to newlyweds; at a wedding; the second section is much more reflective and subdued.

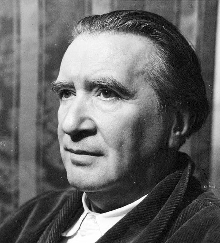

Grieg wrote this for piano. It features as the sixth piece in the eighth book of Grieg’s Lyric Pieces. However, you are going to hear Grieg’s own orchestral arrangement, with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra under Jerzy Maksymiuk.

I suppose the famous marriage in classical music was The Marriage of Figaro. Am I allowed to play just about the best-known aria in the opera? Why not? Here’s Giana Rolandi and Dame Felicity Lott singing Che soave zeffiretto (roughly, What a gentle little breeze) from Act 3. Bernard Haitink is conducting the London Philharmonic Orchestra.

Right, let’s change the mood considerably. In the Marriage of Figaro, the Count tries to compel Figaro to marry a woman who is old enough to be his mother. It turns out at the last minute that she is his mother.

There’s also an attempted arranged marriage in a piece written a good few years after the Marriage of Figaro. That came in 1786; Smetana completed his comic opera The Bartered Bride 80 years later.

It’s a typically complex story set in a village which tells the story of how true love conquers all despite the combined efforts of ambitious parents and a scheming marriage broker. Marenka and Jenik want to marry but her parents want her to marry someone she’s never met. It all works out in the end.

You are going to hear the overture to The Bartered Bride, which somewhat unusually was written before any, or much, of the opera had been written. This is the London Philharmonic Orchestra under Gunnar Staern.

Next comes some more music by Smetana and this gives me the opportunity to do something I generally try to do, play a whole piece rather than just a part or movement.

You are going to hear a three-part suite written by Smetana in 1849. At the time he was 25 and on a three-year stint teaching piano to the children of a nobleman, Count Thun. One of his pupils, Countess Maria, was getting married and as a wedding gift to her Smetana wrote this suite, which he called Wedding Scenes.

Smetana wrote the suite for solo piano but later, in the early 20th century, another Czech composer, Hertl, arranged it for orchestra. I’m going to do something unusual here. I’ll let you hear the first and second parts of the suite as Smetana intended, for solo piano. Czech pianist Jitka Cechova plays this rather jaunty music. It’s the sort of music I don’t think anyone could take exception to.

The opening piece is called Wedding Procession and the second section is called Bridegroom and Bride. After that, you will hear the third part of the suite, called Wedding Festivity, but in its orchestral form, played by the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Robert Stankovsky.

You will surely have heard the next piece at a wedding. Here Comes the Bride, as they say.

The Bridal Chorus comes from Lohengrin, which was first performed in 1850, and which is taken from a story taken from early German romance.

Pagans, a superhuman knight, a noblewoman falsely accused of murder – they’re all there. I think it’s amazing that it’s so frequently used in Christian wedding ceremonies. In fact, there are churches that won’t allow it because of the pagan element to Lohengrin.

Now we’ll have another short piece: Wedding Dance from Swan Lake, played by the Budapest Philharmonic conducted by Zoltan Kovacs.

I now have yet another Wedding Dance from you, written by another Russian composer and taken from another ballet. The composer is Sergei Prokofiev and the ballet is The Tale of the Stone Flower.

It’s his eighth and last ballet, completed in 1953, and premiered posthumously in the Bolshoi Theatre a year later. The ballet is taken from a folk tale from the Ural Mountains. Actually, the plot is pure fairy tale but there have been attempts to reinterpret it as a criticism of the Soviet regime.

This is the Novosibirsk Symphony Orchestra conducted by Arnold Katz.

One of the longest marriages in classical music was that of the violinist Fritz Kreisler and Harriet Lies Worz. She was a New York-born divorcée who was the daughter of a German American tobacco merchant. They met in 1901 while he was sailing back to Europe after an American tour and were married a year later, though they repeated the ceremony three more times because of legal technicalities.

Kreisler and his wife were together for 60 years. Kreisler died in 1962 and Harriet survived him by only 16 months.

After he married Kreisler’s career moved steadily upward. Harriet was much more blunt and organised than her somewhat docile husband, and her influence led him to a stable performing life.

At around the turn of the 20th century Kreisler wrote three short pieces for violin and piano which he called Old Viennese Melodies. They are titled Love’s Joy, Love’s Sorrow and Lovely Rosemary.

They tell the story of love and marriage, though I think it’s doubted if they were inspired by Kreisler’s relationship with his wife, which was a good one.

Anyway, let’s hear Itzhak Perlman.

I have featured some Chinese classical music before and I’m about to do so again. The Mermaid Ballet Suite was drawn from a popular ballet produced in the 1950s, at the height of Mao Tse Tung’s reign. I can tell you nothing more about the music, other than that it contains this piano piece, called Mass Dance at the Wedding. Very energetic it is too.

There’s an aspect of marriage – some marriages – that we haven’t considered … the fact that sometimes one partner may be unfaithful.

It’s an aspect that’s at the heart of Ruggero Leoncavallo’s opera Pagliacci, written in 1892. Pagliacci means Clowns, and the opera is the only one written by this composer that’s still regularly performed. Nellie Melba, Luciano Pavarotti and more famously Enrico Caruso have all performed it, and Caruso made the part of Canio, one of the clowns, one of his signature roles.

At the end of the first act Canio discovers his wife’s infidelity just before he goes on stage to play the part of Pagliaccio, the clown. He’s heartbroken and in a state of torment but he knows that the show must go on. He sings Vesti la giubba, literally ‘Put on the costume’ but often referred to as ‘On with the Motley’, the traditional costume of the court jester.

He sings one of the saddest songs in all opera. His pain exemplifies the notion of the "tragic clown": smiling on the outside but crying on the inside. How often have you seen a clown with painted-on tear running down his cheek.

Let’s hear Enrico Caruso sing the start of this aria in a recording that’s now 111 years old.

For the benefit of non-Italian speakers, what he is singing is something like this…

Act! While in delirium,

I no longer know what I say,

or what I do!

And yet it's necessary... make an effort!

Bah! Are you even a man?

You are a clown!Put on your costume, powder your face.

The people pay, and they want to laugh.

And if Harlequin steals your Columbina,

laugh, clown, and everyone will applaud!

Turn your distress and tears into jokes,

your pain and sobbing into a grimace, Ah!Laugh, clown,

at your broken love!

Laugh at the grief that poisons your heart!

Now we will have something that explores a side of marriage that has echoes in The Bartered Bride.

Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari was born in Venice in 1876 to a German father and an Italian mother. He is best known for his comic operas and we are about to hear the intermezzo from one of them, his best-known work, I quatro rusteghi, written in 1906.

This opera was written in the Venetian dialect, which is why quatro, for four, has only one ‘t’ rather than the usual two.

The name I quatro rusteghi is usually translated as The Four Curmudgeons although the opera is often known in English as The School for Fathers.

The story is set in Venice in the 18th century. Four rather cantankerous, somewhat priggish middle-class husbands vainly attempt to keep their women in order. The four grumpy old men browbeat their wives so much that the women lament the day they married.

What happens is that the men want to arrange a marriage between the daughter of one of their number and the son of another. However, the women are determined that their children should have opportunities to marry for love that they themselves were denied.

You are going to hear an Intermezzo from the opera, played by the BBC Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Gianandrea Noseda.

Edward Elgar wrote Salut d’Amour in 1888 not as a wedding present but as an engagement present for the woman who was to become his wife, Caroline Alice Roberts. He gave it a German name, Liebesgruss, Love’s Greeting, because she was fluent in German. She had already given him an engagement present, a poem, The Wind at Dawn, and this piece was him reciprocating.

You are going to hear it as Elgar originally wrote it, for cello and piano, with Yo-Yo Ma and Kathryn Stott playing. It’s also been re-arranged many times for widely varying instrumental combinations.

Earlier I said the most famous marriage in classical music was probably The Marriage of Figaro. Alternatively, it could perhaps be that of Robert Schumann to Clara Weick. Theirs was a love story that had many manifestations in music, including the next piece, which Robert gave to Clara on their wedding day in 1840.

Was I supposed to give my wife a present when we got married? Nobody told me.

You are actually going to hear two pieces, different versions of the same tune. First, Simon O’Neill, the tenor from New Zealand, will sing with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra. The song is Widmung, or Dedication, and it’s taken from a set of lieder called Myrthen which Schumann wrote as his wedding present in 1840.

You my soul, you my heart,

You my rapture, O you my pain,

You my world in which I live,

My heaven you, to which I aspire,

O you my grave, into which

My grief forever I’ve consigned!

It was a song that Franz Liszt particularly liked and he later rearranged as a beautiful piano solo, called Liebeslied. If you don’t mind hearing the same tune again, you will hear it played by the Russian pianist Olga Rusina. I think that this is a particularly sinuous rendition, played at a tempo that’s considerably slower than any other I’ve heard.

I want to finish today’s programme with a piece that’s wrapped up a good many weddings over the years. In 1879, the French organist Charles-Marie Widor composed his Symphony for Organ No. 5 (he wrote 10 in all) and he subsequently revised it many times. It’s a 35-minute symphony but it’s the last of five movements, which lasts over five minutes, that’s best known because of its use at wedding ceremonies.

Princess Margaret, the Duke of Kent, Princess Alexandra of Kent, Princess Anne, Prince Edward and Prince William all had this toccata played as they came out of the church at the end of their wedding ceremonies.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Weddings and Marriage playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.