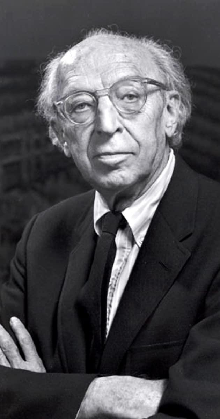

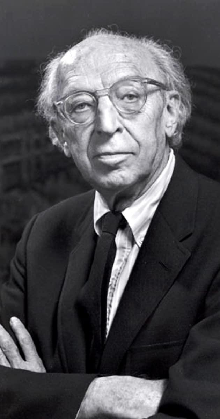

Aaron Copland

The film director Spike Lee once said: “When I listen to Aaron Copland’s music, I hear America. Well, you will be hearing a lot of America today – and a week bit of Mexico. However, you are not going to hear Copland’s best-known work as I’ve used bits of Appalachian Spring in other programmes.

However, by way of compensation, I will play a song that Copland incorporated in Appalachian Spring. Between 1950 and 1950 Aaron Copland arranged two sets of songs after research in the Sheet Music Collection of the Harris Collection of American Poetry and Plays. These songs were originally scored for piano and voice, either mezzo-soprano or baritone. The first set of songs included this, the old Shaker song Simple Gifts.

You will hear a few more of these Old American Songs later.

I don’t plan to give a full biography of Aaron Copland; just a brief potted history. He was born in Brooklyn in 1900, the youngest of five children in a conservative Jewish family originally from Lithuania.

There is a Scottish connection to Copland’s background. His father didn’t emigrate directly to America from Lithuania – he spent two or three years in Scotland first. And Aaron Copland has speculated that his surname was the result of pronouncing the family name, which was Kaplan, with a gruff Scottish accent.

Here’s what he said on the matter:

In 1964 when I was conducting in Glasgow, I noticed that there were more Coplands in the telephone book spelt without an e than with an e. One of the reasons, it seemed to me, was that an o in Scotland is pronounced like a u. They don’t say Scotland, they say Scutland. And they would say Cupland, not Copland... Now if you pronounce the name Kaplan in a Jewish or Russian way, you get almost exactly the same sound and I suspect the transliteration was made there in Scotland and that my father simply took the spelling that they gave him.

Aaron Copland began writing songs when he was eight, took piano lessons as a teenager and at the age of 15 decided he wanted to be a composer. He later went to Paris and studied under Nadia Boulanger, and later returned to New York to dedicate himself to composing.

Boulanger, by the way, had a special interest in American musicians - in the 1910s she developed the conviction that American music was about to "take off," in the way that Russian music had in the generation of Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-Korsakov. Of course, she was right. It was the generation of Copland, Gershwin and their contemporaries who produced much of what we consider the classic American repertoire.

Copland’s first big signature work was El Salón México. Copland visited Mexico several times in the 1930s, and this single-movement piece contains melodies based on sheet music he bought there. Copland began the work in 1932 and completed it in 1936. The Mexico Symphony Orchestra gave the first performance in 1937 and it was premiered in the US the following year. Let’s hear it now. This is Leonard Bernstein conducting the New York Phil.

Copland was a big fan of Stravinsky and it’s been said that the pounding rhythms of The Rite of Spring can be heard in this piece. Copland was proud of this music. He said of it:

It seems a long time since anyone has written an Espana or a Bolero - the kind of brilliant piece that everyone loves.

By the way, El Salón México was the name of an actual dance hall that Copland visited in 1932.

Copland was an enthusiastic traveller, especially to Mexico. He once said about returning to the USA after a trip to Mexico:

As soon as we crossed the border I regretted leaving Mexico with a sharp pang. It took me three years in France to get as close a feeling to the country as I was able to get in three months in Mexico.

Copland's love of travel and sense of tact made him a perfect choice to represent American music abroad - something the State Department invited him to do more than once. Ironically, some of these trips came during the McCarthy years when another arm of the government was decrying Copland for being "unpatriotic."

Copland got the musical ideas for El Salón México in Mexico itself - but part of the actual work on the score took place in Minnesota. When Copland was working out the orchestration, he was enjoying a holiday in a lake-side cabin. So it is that probably the only classical music to come out of Minnesota is a brilliant potpourri of Mexican dance-hall tunes.

El Salón México was a huge public success, and Copland’s reputation was further enhanced when he completed his ballet Billy the Kid in 1938. The story follows the life of the infamous outlaw. It begins with the sweeping song "The Open Prairie" and shows many pioneers trekking westward. The action then shifts to a small frontier town. Billy’s mother is killed by a stray bullet during a gunfight and Billy stabs her killer, then goes on the run.

The next scenes show episodes in Billy's later life. He is living in the desert, is hunted and captured by a posse (in which the ensuing gun battle features prominent percussive effects) and taken to jail. He manages to escape after stealing a gun from the warden during a game of cards and returns to his hide-out, where he thinks he is safe, but sheriff Pat Garrett catches up and shoots him to death. The ballet ends with "The Open Prairie" theme and pioneers once again travelling west.

Let’s hear a couple of pieces from Billy the Kid, again with Leonard Bernstein – who was always a big champion of Copland – and the New York Phil. We’ll begin with the Introduction and then hear a piece called Celebration, which depicts Billy’s capture.

This ballet isn't a historical picture of William Bonney, to give Billy the Kid one of his aliases, but a mythical account of his life and death.

Leonard Bernstein was, of course, a big champion of Copland. "It's the best we've got, you know,” he once said about Copland’s music. Bernstein called Copland "the only composition teacher I ever had."

Referring to Copland's influence on his own music. He said: "There are some actual quotes I can point to. There is a bar in West Side Story that I always cringe at. It's perhaps the most beautiful bar in West Side Story, too, but I always cringe because I know it's Aaron." Copland responded: "I had an idea how you might cringe less. Just send me some of the royalties that you collect!"

After the success of Billy the Kid, the choreographer Agnes d Mille approached Copland with the idea of creating another Western ballet. Copland's first response was, "I've already composed one of those. Can't you do a ballet about Ellis Island?" That ballet never happened.

At around the same he completed Billy the Kid, Copland wrote the incidental music for The Quiet City, a play by Irwin Shaw. He later reworked it into what you are about to hear, a 10-minute composition designed to be performed independent of the play. Here again, Bernstein and the New York Phil.

He was always good for a good quote, was Aaron Copland. He once said: “Listening to the fifth symphony of Vaughan Williams is like staring at a cow for 45 minutes.”

Let's now hear another of the Old American Songs. This is Willard White singing Copland’s arrangement of Long Time Ago.

Here’s another Copland quote:

The whole problem can be stated quite simply by asking, ‘Is there a meaning to music?’ My answer to that would be ‘Yes’. And ‘Can you state in so many words what the meaning is?’ My answer to that would be ‘No’.

Let’s have another short Old American Song. This is Roberta Alexander singing Ching-a-Ring Chaw.

Next up is another piece dating from just before the Second World War, Copland’s An Outdoor Adventure. Copland was commissioned to write some music that he thought would appeal to the American youth – he wrote it for music students at New York’s High School for Music and the Arts. This is an exuberant and optimistic piece of typical Copland Americana.

In 1940, Copland was commissioned to write the music for a film, Our Town, which starred William Holden. Here’s a suite Copland produced from that music, called simply Our Town Suite. In this old recording it’s being performed by the LSO conducted by Copland himself.

Another quote from Copland:

“Composers tend to assume that everyone loves music. Surprisingly enough, everyone doesn’t”.

The 1940s were Copland’s most productive years. His ballet scores for Rodeo and Appalachian Spring were huge successes, as was the Fanfare for the Common Man, another of his best-known pierces of music, written in 1942.

Let’s now hear something from Rodeo, with its piano interlude. Copland called Billy the Kid the first of his ‘Cowboy Ballets’; Rodeo was the second. He was asked to write it by a choreographer, Agnes de Mille. She convinced him with her idea of a simple love story set against the backdrop of American ranch life – what she called ‘The Taming of the Shrew – with cowboys!’

The action centres around Burnt Ranch, where the cowgirl is happy to be just one of the guys, even though she fancies the Head Wrangler. He, like all the other hands, only has eyes for the Rancher’s daughter. Our cowgirl decides on a change of image, puts on a beautiful dress for the hoe down, and finally gets her man.

Another Old American Song now and Roberta Alexander singing The Dodger.

For as long as Billy the Kid and Rodeo have been popular, people have had a field day speculating how a Jewish composer from Brooklyn could write such convincing cowboy music. One fact Copland like to cite in response is that his grandparents had lived in Texas for part of their lives. His grandfather owned a store in Dallas - for a while one of his employees was Frank James.

Let’s have some piano music now. In the 1920s Copland wrote two pieces which he called Piano Blues 1 and 2; in the 40s, he wrote Nos 3 and 4. When he completed the Clarinet Concerto he decided to revise all four pieces, which hadn’t been published, and publish them under the title Four Piano Blues. This is No. 2, played by John Jenson.

Anyone any thoughts on this quote by Copland?

I object to background music no matter how good it is. Composers want people to listen to their music, they don't want them doing something else while their music is on. I'd like to get the guy who sold all those big businessmen the idea of putting music in the elevators, for he was really clever. What on earth good does it do anybody to hear those four or eight bars while going up a few flights?

In 1959, Copland composed a ballet, Dance Panels, for a planned collaboration with the choreographer Jerome Robbins. After Copland wrote the score, Robbins reneged on his commitment and the performance did not take place. Three years later, Copland revised the score for a ballet by the Bavarian State Opera in Munich, Germany, where it premiered in 1963. The concert version of this music received its first performance in 1966. I think it’s one of Copland’s more accessible late scores.

This is the Detroit Symphony Orchestra under Leonard Slatkin playing the pas de trois from Dance Panels.

“A melody is not merely something you can hum”, Copland once said. He also said: “If you want to know about the Sixties, play the music of The Beatles.”

Well, by the 60s, Copland had turned increasingly to conducting, not least because – like a good few other composers before him, he felt he had ran out of new ideas for composition. He said: “It was exactly as if someone had turned off a faucet.”

There’s a story about how Copland's conducting career brought a welcome fringe benefit, in the form of the fees he was able to command. Once, when Copland had bought a new car, a friend of his greeted him by saying, "Aaron, that doesn't look like a composer's car!" Copland responded, "It's not - it's a conductor's car."

It may be that in taking up conducting he was acting on the advice of a friend, who once told him: "Aaron, it is very important, as you get older, to engage in an activity that you didn't engage in when you were young, so that you are not continually in competition with yourself as a young man."

Anyway, Copland became a frequent guest conductor in the United States and the UK and made a series of recordings of his music.

From the 1960s to his death he lived in a house called Cortlandt Manor in New York State. It’s now a National Historic Landmark, as befitting a man who provided much of the soundtrack to 20th century America. Aaron Copland died of Alzheimer’s and respiratory failure in 1990, just a few days after his 90th birthday.

Let’s hear one more small orchestral piece. Copland enjoyed the challenge of composing for young performers. Life Magazine commissioned a piano piece and featured it in a 1962 issue of the magazine with photographs and a homespun article that explained, "Copland's Down a Country Lane fills a musical gap. It is among the few modern pieces specially written for young piano students by a major composer."

I find the original piano version to be somewhat sparse, so I’ve found this orchestral version, again with Copland himself conducting the LSO. This is Down a Country Lane.

Finally, I like this quote by Copland:

Finally, I like this quote by Copland:

“If a literary man puts together two words about music, one of them will be wrong.”

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Aaron Copland playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.