Africa

Africa may not be the obvious subject for a programme on classical music, but there is actually no shortage of very fine music I have been able to draw on that relates in one way or another to the continent.

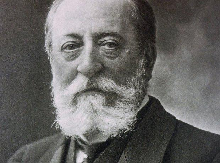

In an earlier programme I talked about Saint-Saëns’ love of North Africa. He travelled there frequently and I recently played a piece by him which supposedly depicted his journey on a Nile cruise ship.

Well, I thought I would start today with another piece by Saint-Saëns, this one called Suite Algerienne. Saint-Saens loved Algeria – he actually died there - and the theme for the third movement of this four-movement suite came from his first visit there in 1873.

He composed a single-movement Rêverie orientale, which was performed in Paris 1879, as a fund-raiser for victims of a devastating flood in Algeria. His publisher then asked him to write more pieces like it. So in 1880, Saint-Saëns composed three other movements.

This, then, is the third movement of his Suite Algerienne, which has the overall sub-title Picturesque Impressions of a Voyage to Algeria. The third movement he called An Evening Dream at Blidah, a fortress near Algiers. It’s a quiet and quite romantic piece – a nocturne, we might call it.

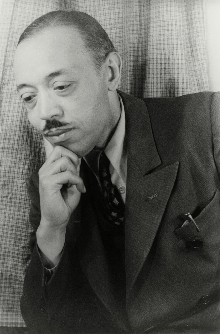

I now want to introduce you to someone whose music I had never heard before I started researching this programme, the African-American composer William Grant Still.

He was born in Mississippi in 1895 and grew up in Little Rock, Arkansas, a heartland of segregation in the United States and the birthplace of another African American composer, Florence Price. His father was a bandleader and he taught himself to play the clarinet, saxophone, oboe, double bass, viola and cello. He knew his music and was good at it.

He notched up a good few ‘firsts’ in his time: the first African American composer to have an opera produced by New York City Opera; the first to conduct a major American symphony orchestra; the first to have an opera performed on national television.

He is best known for his first symphony, The Afro-American, which he wrote in 1930 and which is heavily influenced by the blues. In the same year he completed a symphonic poem he called Africa. It was a work he had wrestled with for 10 years. He never visited Africa so this piece represented what he called ‘the Africa of my imagination’. It’s in three movements, and you are going to hear the middle one, which he called Land of Romance. It begins quite serenely with the bassoon and builds to a climax reminiscent of the moment when the sun rises in Debussy’s La Mer. Let’s hear that movement now.

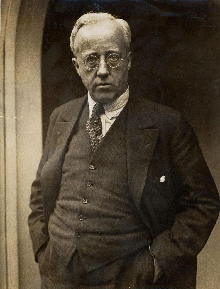

In January 1956 William Walton was commissioned to write a piece to mark the 70th anniversary of the founding of Johannesburg. Never having been to Africa, for inspiration he asked for recordings of African music from the African Music Society. The effect of these recordings can be heard with three percussionists performing on 11 instruments. We have timpani, side drum, cymbals, suspended cymbal, bass drum, xylophone, tambourine, triangle, tenor drum, maracas, rumba sticks, castanets, glockenspiel.

Walton described the piece to his publisher as “a non-stop gallop...slightly crazy, hilarious and vulgar”. I think it is a portrait of an African city in English guise, fit music for an English Commonwealth nation. But, to be fair, halfway through the overture, he introduces percussion parts adding a most un-English flavour.

For the premiere, Malcolm Sargent conducted the South African Broadcasting Corporation Symphony Orchestra in a broadcast from City Hall in Johannesburg.

So let’s hear the Johannesburg Festival Overture.

Now for a piece that I’ve included with a degree of trepidation. You see, it’s quite a contemporary piece and I’m not at all sure it’s necessarily everybody’s cup of tea. Nevertheless, it did something for me when I first heard it, so hear it is. It also gives me the opportunity to take this programme to West Africa.

In 1990, when he was 85, Sir Michael Tippett went on a holiday to Senegal and it was suggested to him that he visited a small body of water called Lake Retba but known generally as Le Lac Rose, the Rose Lake. He later wrote:

At midday the impact of the sun was such as to transform its whitish green colour to whitish pink. As things turned out we reached Le Lac Rose at midday, just in time to see it turn a marvellous translucent pink. The sight of it triggered a profound disturbance within me: the sort of disturbance which told me that the new orchestral work had begun.

Apparently, the rose colour is caused by an algae which produces a red pigment. The colour is particularly evident during the dry season, from November to June.

What really interested Tippett was the relationship between the lake and the sky. I suppose like Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony or Debussy’s La Mer, The Rose Lake is concerned with expressions of feeling rather than description. Michael Tippett’s last orchestral work and is a shimmering response in musical terms to what he saw. There’s a light, almost transluscent quality about the music and a tangible sense of atmosphere.

Tippett completed The Rose Lake in 1993 and the first performance, at London's Barbican Centre in 1995, was a memorable occasion not least because the concert was staged to celebrate Tippett’s 90th birthday. Although Tippett had already said it would be his last major work, what might have been a nostalgic evening turned out to be anything but for it was quickly recognised that here was a substantial orchestral work to rank with the best the composer had written.

Tippett died three years after the premiere.

Sir Colin Davis was a champion of this work and you are going to hear The Rose Lake performed by the London Symphony Orchestra with him conducting.

The music comes in short sections and each having a name, such as The Lake Begins to Sing and The Lake Song is echoed. I fought this piece when I first heard it but played it a few times since and would suggest this. Apart from its colour, the Rose Lake is unusual in that it has a particularly high salt content – around 40 per cent – which makes it easy to float on. So just float on the music and think about Christmas, or Brexit or the price of cheese.

This entire work is about half and hour long but I will play only half of it so that I have time for more music. So I will skip most of the second half of the piece but will include the final scene

We have just heard a piece inspired by a place in Senegal and we are going to stay in Senegal now. In the 1720s, a girl was born in a village in what is now Senegal. Some time later, slavers took the girl into captivity and, in time, she endured a dreadful voyage across the Atlantic to the West Indies.

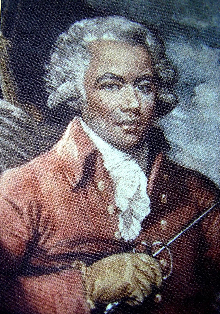

The girl, whose name was Anne dites Nanon, was bought by a man called Georges de Bologne Saint-Georges, who was a councillor in Metz and who was a wealthy landowner and planter in Gaudaloupe. She became personal maid to Georges’ wife, Elisabeth, and in 1745, when she was 16, she became pregnant, courtesy of her master, and gave birth to a boy. Although Georges was married and a slaver, he acknowledged the boy as his son.

In France, Georges was well connected to royalty: he was officially known as a Gentleman of the King’s Chamber. Needless to say, his black son was not eligible for any titles of nobility due to his African mother. However, his wealthy father determined to give the boy every opportunity in life and when he was seven he was placed in a boarding school in France. Later, he went to a military academy where he became an excellent swordsman and, in time, an officer of the king’s bodyguard.

The boy was also an extremely gifted musician. He could play the violin very well and soon became part of the concert scene. One source wrote:

The celebrated Saint-Georges, mulatto fencer and violinist, created a sensation in Paris where he was appreciated not as much for his compositions as for his performances, enrapturing especially the feminine members of his audience.

And so Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges, became a champion fencer, virtuoso violinist, classical composer and conductor of the leading symphony orchestra in Paris. He also became music teacher to Marie Antoinette and often played for her.

And he became a solider. During the French Revolution, he served as a colonel in the first all-black regiment in Europe, fighting on the side of the Republic.

Bologne, the first known classical composer of African ancestry, composed numerous string quartets and other instrumental music, and opera. He was known as ‘the Black Mozart’. In fact, so talented was he that it was suggested that Mozart should be called the ‘White Joseph Bologne’.

There is evidence that Mozart and Bologne, who were only a few years apart, weren’t exactly best friends. Mozart had his prejudices, but against French people rather than black people. He and his mother spent some time in Paris when he was in his 20s, and he hated it and the French. He wrote that they were “frightfully arrogant” and he was appalled by their general immorality.

It’s also believed that he was extremely jealous of Bologne, who was making it big in French society while he, Mozart, struggled to get his foot in the door of that world. For a while, the two men were guests in the same house. Mozart was 22 and at rock bottom, struggling financially, struggling with the language and struggling to make a name for himself in France. Bologne, meanwhile, was, according to American president John Adams, “the “most accomplished man in Europe”. He was 33, exotic, brilliant, established, a favourite with the ladies and close to the Queen.And as a composer, he was very highly regarded. In fact, Mozart copied note-for-note from a Bologne violin concerto for a piece he wrote for a short ballet. And in France today, there are those who regard his music as comparable to Mozart’s.

Let’s hear some of his music. This is the opening movement of his Violin Concerto No. 9. This piece, which like almost all of his music he composed for his own use, was written in around 1778.

We’ve heard some Walton and some Tippett and I have another English composer next, and it’s Gustav Holst.

In 1908 Holst had a holiday in Algeria on medical advice. He had been told that his opera Sita was awarded a third prize in the Ricordi Competition, thus not winning a cash prize nor guaranteed a performance. Sita had taken up all of Holst's spare time for the best part of six years and, now without extra revenue, he doubted his credibility as a composer.

His friend, Ralph Vaughan Williams gave him some money and reinforced his doctor’s opinion that he needed to go on holiday to a warm place to help his health. He had asthma, neuritis and depression and it was felt a break in the sun would do him good. And so, aboard an iron bike, he explored the mountains and deserts of Algeria. It’s said that in Algeria Holst listened to a street musician play the same phrase on a bamboo flute non-stop for two hours, inspiring part of this suite of three movements.

You can hear how this flute episode influenced this piece in the third movement. I think Holst scented a musical challenge and he introduces a short evocative riff in the low flute. I could suggest you count how many times he repeats this but I’ll tell you. You will hear it a mere 163 times. It creates a hypnotic atmosphere of highly charged night air vibrating as the sounds of an approaching Arab procession mingle with those from the dance halls and cafés lining the street.

This, then, is the three-movement Beni Mora, sub-titled Oriental Suite for Orchestra, regarded as Holst's first mature orchestral piece.

Vaughan Williams wrote of this music, "If it had been played in Paris rather than London it would have given its composer a European reputation and played in Italy would probably have caused a riot. Holst would have gained fame a good 10 years before The Planets made him a household name.”

When I first wrote this programme I chose something of an oddity, a piece I suppose is called Casablanca Suite. It’s a compilation of excerpts of music from the 1942 film Casablanca. However, after playing it a few times I can’t escape the notion that its an incoherent hodge-podge of tunes. I will tell you something about the music for Casablanca though.

Max Steiner, the Austrian-born American composer, wrote the score for the film though he didn’t compose probably the best-known number from the film, As Time Goes By, which was written by Herman Hupfield and which Steiner hated.

Steiner wanted to write his own composition to replace it, but the actress Ingrid Bergman had already cut her hair short for her next role (María in For Whom the Bell Tolls) and could not re-shoot the scenes which incorporated the song, so Steiner was left with no choice but to base the entire score for the film on both As Time Goes By and La Marseillaise, the French national anthem.

Incidentally, the "piano player" in the film, Dooley Wilson, was a drummer and not a trained pianist, so the piano music for the film was played offscreen by Jean Plummer and dubbed.

OK, then, having rejected Casablanca I decided to play a piece of music from Africa, and I’ve picked something performed by an African. The soprano Pumeza Matshikiza was born in South Africa just 30 years ago. She studied in Cape Town and then, courtesy of a three-year scholarship, at the Royal College of Music in London.

Pumeza Matshikza’s first major role as an operatic singer was that of Mimi in La Boheme in the 2010 Edinburgh Festival, a production by a new company, Opera Bohemia. At the time she was principal young artist from the Royal Opera House Covent Garden and she was without the star of the show in this production.

So let’s hear her as Mimi singing. Si. Mi Chiamano Mimi.

Now we’ll hear her singing something from her homeland. This is Thula Baba, Hush, My Baby, a Zulu lullaby.

Finally, I’d like to wrap today’s programme with a piece called simply Africa – and appropriate ending, I think. We’re going back to Saint-Saëns again. He began work on this very colourful fantasy for piano and orchestra in Cadiz in 1889 and completed it in Cairo in 1891.

Saint-Saëns was in Africa at the time in need of convalescence after serious illness and the death of his mother, His study of North African folk music is reflected in this piece, the climax of which is based on a Tunisian folk tune.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Africa playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.