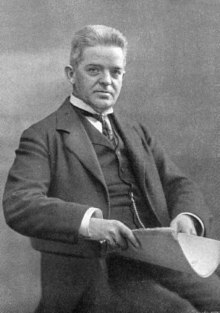

Carl Nielsen

This programme is about the life and music of the Danish composer Carl Nielsen and I thought I’d begin, before I say any more, with something that’s an appropriate way to start: with an overture.

That was the Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Ulf Shirmer playing Carl Nielsen’s overture to Maskerade, which is considered to be Denmark’s national opera – although it is based on a comedy written by a Norwegian, Ludvig Holberg.

In 2006, Denmark's Ministry of Culture named the opera one of the country’s 12 greatest musical works. Incidentally, two other works by Nielsen featured in the top 12. For all that Maskerade became hugely popular in Denmark, Nielsen himself wasn’t happy with the work, although he never got round to revising it.

The overture you heard is one of Nielsen’s most widely performed works worldwide.

Carl Nielsen, who was born in 1865 and died at the age of 66 in 1931, is Denmark’s most prominent composer. He wrote six symphonies, several highly regarded concerti, a huge number of songs, chamber pieces, solo works for piano and organ, and a couple of operas, Maskerade and Saul and David.

Now, let’s hear more music. Next comes Tit er jeg glad, a stunning melody composed by Nielsen in 1917 to words written almost 100 years earlier by a then love-struck Danish poet, Bernhard Severin. I have found an English translation of this poem, although it was translated into English from, of all things, a Welsh translation of it. It begins…

Sometimes I’m glad but often want to cry

There is no-one to share the happy days

Sometimes I’m sad but then I’m bright all over

so no one notices my bitter tear\

As you will hear, it’s a spare and moving melody. Nielsen wrote hundreds of songs and if they're all as beautiful as this, they should be way better known. I read a comment online which said: “This sounds like Brahms, Bruckner and Elgar all rolled into one. You need this song in your life…”

Carl Nielsen was born the seventh of 12 children into a poor peasant family in the island of Funen. His father Niels was a house painter and a traditional musician who played the fiddle and cornet, and his mother would often sing local folk songs in the family home. She gave him a violin when he was six, and he later learned to play it and the piano. He was writing music by the age of eight or nine.

As his parents did not believe he had any future as a musician, they apprenticed him to a shopkeeper from a nearby village when he was 13; fortunately for music, the shopkeeper went bankrupt and Nielsen had to return home.

After learning to play brass instruments, when he was 14 he became a bugler and alto trombonist in a Danish army band. Nielsen did not give up the violin during his time with the battalion, continuing to play it when he went home to perform at dances with his father.

Let’s have some more music now. You are going to hear the intermezzo from Nielsen’s Opus No. 1, his Little Suite for Strings, played by the Academy of St Martin in the Fields under Sir Neville Marriner. It begins, as you will hear, with a lilting waltz that morphs into a more energetic dance section.

Nielsen wrote this when he was 23. The programme notes for the premiere of this suite in 1888 described the composer as “Mr Carl Nielsen, whom nobody knows.”

A review of the premiere described this intermezzo as “the jewel of the suite”.

By the time he was 26 Nielsen was studying the violin seriously and he was released from the military band to attend the Royal Academy in Copenhagen. He left the academy three years later, graduating with good if not outstanding marks in all subjects. In time he secured a position with the second violins in the prestigious Royal Danish Orchestra.

The next piece you are going to hear is the second movement of Nielsen’s first symphony, which he wrote in 1892, while he was still at the academy. He dedicated the work to his wife Anne Marie, a sculptor, whom he married a year earlier. The symphony was premiered in Copenhagen in 1894.

It’s not unusual for a composer to be present at the world premiere of his new piece. It’s not even all that odd for him to participate in the performance — usually as the conductor. The audience at the premiere of Carl Nielsen’s first symphony could be forgiven, though, for wondering why a member of the second violin section was taking a bow at the conclusion of the piece. On realising who it was, they demanded no fewer than three curtain calls from the composer. Nielson earned a living as an orchestral violinist for 16 years.

Next we will hear a very short piano piece by Nielsen played by the English pianist John McCabe.

That was a Humoresque, one of five piano pieces, Nielsen’s opus No. 3, written in 1890.

The 1st Symphony was a big success and a string of commissions came Nielsen’s way. He found himself writing pieces for theatrical productions and cantatas for special occasions, while also teaching piano privately. He subsequently became second conductor for the Royal Danish Theatre, and in 1916 he took a teaching post at the Royal Danish Academy of Music and continued to work there until his death in 1931.

I’d now like to play something from another of Nielsen’s six symphonies. He called his 3rd Symphony his ‘Sinfonia espansiva’, and it was regarded as something of a breakthrough for Nielsen. It was premiered by the Royal Danish Orchestra in Copenhagen in 1912, and within six months was being played by the Royal Concertgebouw in the Netherlands. It is unique in among Nielsen’s symphonies for having vocal parts, wordless solos for offstage soprano and baritone in the second movement, which I’ll play now... complete with its unusual vocal contribution.

If that movement ended in somewhat unusual fashion, the entire symphony begins unusually too. It starts with a bang … well, 26 bangs actually, with the same note repeated, before launching into a somewhat urgent theme. Listen to just the first few seconds, which reminds me of the end of Sibelius’s 5th Symphony.

I mentioned earlier that Nielsen composed several excellent concerti. His flute concerto, which was premiered in Paris in 1926, is a joy, and he wrote a well-received violin concert some 15 years earlier.

However, I have chosen the third of his concerti, his Concerto for Clarinet, the beginning of which you are going to hear played by the German musician Sabine Meyer with the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Simon Rattle.

I say the beginning because the concerto was written as one continuous movement, but you are going to hear only the opening – allegretto un poco.

The Clarinet Concerto was conceived during the most difficult period in Nielsen's life. In 1928 he was 63, and his work was appreciated throughout Scandinavia; yet he was disappointed that his music had not reached a wider audience, he was deeply concerned with the unsettled state of the world, and he knew that his days were numbered.

Perhaps this accounts for the bitter struggle which occurs throughout this concerto — a war between F major and E major. This battle between keys is something that’s common in Nielsen’s work. Every time hostilities seem to be at an end, a snare drum incites the combatants to renewed conflict.

What happened was that Nielsen was ordered by his doctor to rest following ongoing heart problems. He decided to rest by taking a ski-ing trip to Norway with his wife, in which he managed to break a couple of ribs. He started work on the concerto while in Norway.

Eventually Anne Marie continued on to Carrara in Italy to resume work on her latest project – remember, she was a sculptor and doubtless had a thing about Carrara marble – while Nielsen travelled back to Denmark to finish the concerto.

He wrote to a friend: “I actually have no idea how it will sound. Maybe it won’t sound good, but I will not compose music if I always have to compose in the same manner.”

Nielsen’s son-in-law conducted the premiere before a selected audience and described it as “music from another planet”. One critic described the piece as “absolutely the worst thing that this slightly too obviously experimental and provocatively sidestepping Dane has yet put together”.

Nielsen died just under three years after he completed this concerto, and it was his last major orchestral work. It’s a brilliant and sparky piece.

This, then, is the opening movement.

Some piano music next. Nielson’s Opus No. 11, written in 1897, is a what he called Humoresque Bagatelles, a set of six short pieces. It’s felt that they were written with his children in mind as they are called ‘Hello! Hello!’, ‘The spinning top’, ‘A little slow waltz’, ‘The jumping jack’, ‘Puppet march’ and the musical clock’.

Let’s hear all six, played by the English pianist and composer John McCabe.

I would like to change the mood a bit and play something from Nielson’s Aladdin Suite. He wrote this suite in 1919 to accompany a new, “dramatic fairy tale” stage production of Aladdin. It’s a long suite – about 80 minutes – and like Tchaikovsky’s ballet suites it features music for dances from various parts of the world. There’s a Hindu dance, a Negro dance, a Chinese dance, and so on.

Nielsen himself frequently conducted extracts from Aladdin to great acclaim both in Denmark and abroad. He had been scheduled to conduct extracts with the Radio Symphony Orchestra on 1st October 1931 when he suffered a major heart attack.

Lying on a hospital bed, he was nevertheless able to listen some extracts from the suite on a crystal set before he died the following day. These extracts were published in 1940 as the Aladdin Suite.

This is the first of the suite’s seven parts, the Festival March, played by the South Jutland Symphony Orchestra conducted by Niklas Willen.

It’s a co-incidence that that recording is by the South Jutland Symphony Orchestra because the next piece was prompted by South Jutland. The area known as South Jutland was once divided into two parts, North and South Schleswig. In 1920 it was agreed that the southern part should remain part of the German state of Schleswig Holstein and the northern bit part would go to Denmark.

A gala was held the following year to celebrate Denmark getting, or rather reclaiming, South Jutland, and Nielsen wrote music for the occasion. The gala took the form of a play based on a set of patriotic verses. The play is a fairy-tale allegory about the return of a kidnapped son. A beautiful melody for flute and harp, The Fog is Lifting, accompanies the first scene in which a mother is seen parting from her son through the rising fog.

Four of Neilson’s six symphonies had names. You’ve heard something from the 3rd, the Symphonia Espansiva. The second he called The Four Temperaments, the sixth Simfonia Semplice and the fourth The Inextinguishable.

This, the fourth symphony, was written during the dark days of World War One. Nielsen described the title, The Inextinguishable as expressing "the appearance of the most elementary forces among human beings, animals and even plants. We can say in case all the world were to be devastated by fire, flood or volcanoes and all things were destroyed and dead, nature would still begin to breed new life again, begin to push forward again with all the fine and strong forces inherent in matter. These forces, which are inextinguishable, are what I have tried to present."

You don’t really get a sense of that in the second movement, which you are about to hear Actually, the symphony is a continuous piece and it’s not obvious where one movement ends and the other starts.

That said, I will play without a break the charming and quite playful second movement, which sounds as if it might have come from the 18th century, and then the last movement, which features something of a battle between timpanis but which ends in victory.

This is the London Symphony Orchestra under Sir Colin Davis.

There’s something unsettling about all Nielsen’s symphonies. The sixth features a movement for just wind and percussion instruments that has absolutely no melody. Oh, and it ends with a big raspberry by a bassoon. And in the fifth a drummer is required to play off-stage. Once, when the BBC Symphony Orchestra was playing it in Munich, an over-zealous usher tried to stop the percussionist playing his drum off stage. “You can’t play that here,” he told him. “There’s a concert going on”.

We had a song early in today’s programme and I’d like to finish with one, a choral work called Evening Mood, which Nielsen wrote in 1908.

The woods are dimly listening,

The golden stars are glistening

In heaven mild and pure;

As nature is exhaling,

At eventide goes sailing

A misty whiteness o’er the moor

How calm the Earth reposes

In veils of night, and dozes

From summer warmth so deep;

Like such a shrine you see it

While mis’ry is – so be it –

Forgotten in the arms of sleep\

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Carl Nielsen playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.