Loneliness and Longing

This programme is called ‘Loneliness and Longing’, and if that sounds a bit sad, well, so be it. But being lonely is a condition we have all experienced, and it’s no wonder it’s provided the inspiration for some very moving music.

Similarly, longing – that feeling, sometimes unrequited, of wanting something or someone very much – is the central theme of a great deal of music and opera.

And it’s with opera we’ll start, and the Austrian composer Erich Wolfgang Korngold’s Die Tote Stadt, The Dead City, which he wrote in 1920 when he was only 23.

The "dead city" in the opera's title is Bruges, Belgium. At the start of the opera, Paul confides in a friend the extraordinary news that he has seen his dead wife, Marie, or her double, in the town and that he has invited her to the house. She arrives, and Paul addresses her as Marie, but she corrects him: she is Marietta, a dancer from Lille.

He is enchanted by her, especially when she accepts his request for a song, Glück das mir verblieb, Joy, that near to me remains. The words of this duet tell of the joy of love, but there is a sadness in it also because its theme is how life is a very transitory thing. Their voices combine in the verse which extols the power of love to remain constant in a fleeting world.

Here’s a translation of the song...

Happiness that has stayed with me,

move up close beside me, my true love.

In the grove evening is waning,

yet you are my light and day.

One heart beats uneasily against the other,

[while] hope soars heavenward.\ How true, a mournful song.

The song of the true love

bound to die.

I know this song.

I often heard it sung

in happier days of yore.\ Though dismal sorrow is drawing nigh,

move up close beside me, my true love.

Turn your wan face to me

death will not part us.

When the hour of death comes one day,

believe that you will rise again.\

This is an opera that’s entirely about longing. Here we have the soprano Tatiana Pavlovskaya and the tenor Klaus Florian Vogt singing the duet.

I don’t know if the next piece was necessarily written with loneliness and longing in mind but it’s certainly the case that a sense of sadness pervades the piece. Let’s put it this way: I don’t know what was in Brahms’ mind when he wrote it but he certainly hadn’t just won the lottery.

Brahms wrote his Clarinet Quintet in B Minor in 1891, after he took the decision to retire from composing.

Some people feel it’s Brahms’ most profound chamber piece, although there are a good few pieces that would rival it I think the clarinet lends the piece an autumnal, melancholic sound that’s maybe appropriate given that Brahms died only a few years after it was written.

He may have been at the twilight of his career but he was at the height of his powers, as you will hear in this, the beautiful second movement, with the Swede Martin Frost playing the clarinet.

You are going to hear quite a bit of the human voice this morning but given that there is no better classical instrument that’s no bad thing.

Mahler’s Rückert-Lieder is a cycle of seven songs published in its entirety 1910. The song you are going to hear is Mahler’s best-known, ‘I am Lost to the World’. As always with poetry, it’s not easy to translate, but I found what seems to be a reasonable English translation.

I am lost to the world

with which I used to waste so much time,

It has heard nothing from me for so long

that it may very well believe that I am dead!

It is of no consequence to me

Whether it thinks me dead;

I cannot deny it,

for I really am dead to the world.

I am dead to the world’s tumult,

And I rest in a quiet realm!

I live alone in my heaven,

In my love and in my song!\

It’s a poem by Friedrich Rückert (1788-1866) which Mahler set as the fourth song of his Rückert Lieder in the summer of 1901. Mahler was personally drawn to the poem, which speaks of the solitary world of the artist - a mysterious place where fantasy and reality are inseparable.

I read a description of this song which sounds like a public health warning: “Even by Mahler’s standards, it’s magnificently morose.”

This is Anne Sofie von Otter, with John Elliot Gardiner conducting the NDR Symphony Orchestra.

Tchaikovsky next and None but the Lonely Heart, a setting, written in 1869, of a poem by Goethe. However, there are no vocals in the recording you are going to hear. There are countless arrangements of this and I’ve chosen one where the viola, in the hands of the English player Helen Callus, is to the fore.

The words of the poem are exactly what today’s programme is all about:

None but the lonely heart

Can know my sadness

Alone and parted far

From joy and gladness\

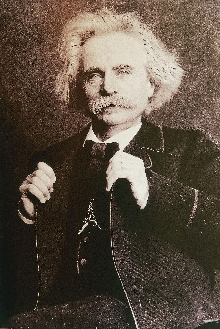

You are now going to hear a lovely piano piece by Edvard Grieg from his Lyric Pieces, a collection of 66 pieces for solo piano published in 10 volumes from 1867 to 1901.

There’s quite a bit of loneliness and longing in Lyric Pieces. One of the compositions, for example, is called The Lonely Wanderer, which comes from Book 3, which means it was probably written in 1863. Book 6 features a piece called Homesickness, a longing with which I suppose we’ve all been familiar with at some time or another.

I really like this music. Listen out for the contrast between the mournful opening theme, which expresses the feeling of homesickness, with a brief interlude of energetic and seemingly cheerful music, followed again by the opening theme.

The pianist is the Spaniard Javier Parianes, who recently appeared with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra for their season opening concerts at Perth Concert Hall, where he performed Brahms’ Piano Concerto No. 1.

More opera now and a piece that you will know but you may not know what it’s about. Actually, it has the same theme as the last piece: homesickness.

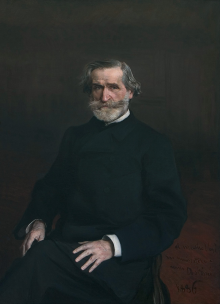

Verdi’s Nabucco follows the plight of the Jews as they are conquered and subsequently exiled from their homeland by the Babylonian king Nabucco.

The best-known number from it, of course, is the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves, ‘Va, pensiero, sull’ali dorate’, ‘Fly, thought on golden wings’. It’s the slaves’ lament for their lost homeland, but it may be a bit more than that.

First, a wee story about Nabucco. Verdi wrote it at a particularly bad time in his life. His young wife and two children had all just died of various illnesses and it’s said he decided to abstain from opera writing. However, he had been contracted with La Scala to write another opera and the director forced the libretto into his hands.

Returning home, Verdi happened to open the libretto at "Va, pensiero" and, seeing the phrase, he heard the words singing. Verdi later wrote that "this is the opera with which my artistic career really begins. And though I had many difficulties to fight against, it is certain that Nabucco was born under a lucky star".

Verdi died in 1901, and along his funeral's cortege in the streets of Milan, bystanders started spontaneous choruses of "Va, pensiero". A month later, when he was reinterred alongside his wife at the Casa di Riposo, a young Arturo Toscanini conducted a choir of 800 in the famous hymn.

And that hints at the mystery or myth about this song. Some folk believe that the chorus was intended to be an anthem for Italian patriots, who were seeking to unify their country and free it from foreign control in the years up to 1861. The chorus's theme of exiles singing about their homeland, and its lines like "O mia patria, si bella e perduta" / "O my country, so beautiful, and lost" was thought to have resonated with many Italians. It has even proposed that this song be Italy’s national anthem – an idea most recently dismissed in 2009. It is, however, the anthem for a political party, Lega Noda.

Let’s hear the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves sung by the London Philharmonic Choir and The London Chorus.

Now another piece that I know may well be familiar to you. Franz Liszt’s Liebestraume, Dreams of Love, is a set of three piano nocturnes. The third, which you are about to hear played by John Ogdon, is a setting of a poem, Lieb, so lang du lieben kannst (Love as long as love you can), that depicts love and the loss of love.

Liszt set the poem to music for soprano voice and piano, and eventually adapted it into his famous Liebesträume No. 3, one of Liszt's most famous and poignant pieces.

It’s a long poem which begins:

O love, love as long as you can!

O love, love as long as you may!

The time will come, the time will come,

When you will stand at the grave and mourn.\

Be sure that your heart burns,

And holds and keeps love

As long as another heart beats warmly

With its love for you \

And if someone bears his soul to you

Love him back as best you can

Give his every hour joy,

Let him pass none in sorrow!\

This is heart-wrenching and troubled music, which starts with the hopeful promise of love. That hope dies with the death of a loved one.

When I first prepared this programme I included in it a piece by Gustav Holst called Egdon Heath.

In 1927 Holst went for a walk with Thomas Hardy on Slepe Heath, an empty, featureless bit of countryside in Dorset. The walk provided the inspiration for a composition he called Egdon Heath: A Homage to Thomas Hardy. It was premiered the following year three weeks after Hardy’s death, so the writer never heard it.

Actually, the place, Egdon Heath, doesn’t exist. It’s a fictional place that Hardy invented to represent heathland in another place that’s in part fictional, Wessex, where Hardy set his novels. It features in The Mayor of Casterbridge and it provides the setting for The Return of the Native. This is a barren and lonely place that’s rife with witchcraft and superstition.

Egdon Heath is a sparse piece of music, for sure. Like the heath Holst and Hardy explored together, it’s desolate and bleak.

However, after first preparing this programme I got to thinking: if I wanted music that was desolate and bleak, why use Holst when I could use Shostakovich? Holst’s imaginary heathland in a corner of England is one thing but the desolate prairies, the chilling Russian Steppes of Shostakovich’s darker moments, are of an entirely different order.

It’s certainly the case that Shostakovich was capable of producing music that’s light, charming, even playful, but when it comes to loneliness and longing, well, he’s the master.

I could have chosen any number of pieces by Shostakovich for this programme but I’ve picked his 15th string quartet.

Shostakovich died of lung cancer and a few other ailments in August 1975 and much of his later work is infused with a sense of despair and mortality. There’s even a suggestion of a longing for death in his work – it’s known that on at least one occasion he made preparations to commit suicide.

His string Quartet No. 15, his final and longest string quartet, was started in February 1974 and completed three months later in a Moscow hospital. The quartet is written in the morbid key of E flat minor.

The quartet has six adagio movements. Much of it is agonisingly slow, but nevertheless beautiful, spare and concentrated. The overall effect is of a series of different ways of saying farewell or taking leave of the world. Even of longing to take leave of the world.

And it came with a most curious instruction as to how it should be performed. Shostakovich wrote: “Play the first movement so that flies drop dead in mid-air and the audience leaves the hall out of sheer boredom.”

Let’s see how many of you leave before this, the first movement, finishes. This is the Rubio String Quartet.

We are now going to hear Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau singing something from Schubert’s Winterreise, winter’s journey, is a remarkable body of work: two groups of 12 songs for voice and piano written in 1827. It’s gloomy, full of heartbreak, grief and pain, perhaps understandably so given that Schubert was dying of syphilis when he wrote it. He actually died the following year.

It’s more than a collection of songs. It’s a single dramatic monologue, lasting over an hour in total. Schubert described Winterreise as being “truly terrible, songs which have affected me more than any others”.

The songs take the audience on a journey that it is clear from the outset will end fatefully. Even the title, “winter’s journey”, conjures up a visual image of a cold and dark landscape.

The lyrics are poems by Wilhelm Müller and tell the story of a lonely traveller who ventures out into the snow on a journey to rid himself of his lost love. Along the way he experiences a turmoil of emotions, ranging from despair to even greater despair.

One of the songs is called, simply, Loneliness. Our traveller wanders, like a sad and lonely cloud, through the bright and happy life around him. "Even when the storms were raging. I was not so miserable."

However, you are going to hear a song called Der Leiermann, The Hurdy-gurdy man. It’s the last of the 24 songs and in in our wandering protagonist encounters a down-and-out street musician, a hurdy-gurdy man.

The poor man, a musically talentless beggar who like our traveller is also alone and lonely, is cranking his instrument with frozen fingers. His begging bowl is always empty; no-one listens to his music, and dogs growl at him. But his playing never stops.

Our wanderer sings:

Just beyond the village

stands a hurdy-gurdy man,

and with numb fingers

he plays as best he can.\

Barefoot on the ice

he totters to and fro,

and his little plate

has no reward to show.\

No-one wants to listen,

no-one takes a scan,

and the dogs all growl

around the aged man.\

And he lets it happen,

as it always will,

grinds his hurdy-gurdy;

it is never still.\

Curious old fellow,

shall I go with you?

When I sing my songs,

will you play your hurdy-gurdy too?\

The more I listen to this song the more I think of this song. Why not give this just a few seconds?

Bob Dylan’s Mr Tambourine Man and his jingle-jangle and Schubert’s hurdy-gurdy man are surely related. Let’s hear the Schubert now...

Rusalka is an opera by Dvorak that is about singing. Or rather, what happens when you cannot sing. Rusalka, a lonely nymph, gives up her voice to be united with a prince. But he is distinctly put out when his bride-to-be cannot say a word. Instead he accepts the hand of a foreign princess and Rusalka, obeying the witch Ježibaba’s curse, is doomed to live in the depths of the lake forever.

The aria 'Song to the Moon' comes right at the beginning as Rusalka, as a nymph, sings to the moon, longing it to tell the prince that she longs for him. This beautiful song tells us of the tragedy at the heart of the opera. The prince may swim in the lake, but he’s never heard Rusalka sing and, if she becomes a human, he never will.

O moon high up in the deep, deep sky,

Your light sees far away regions,

You travel round the wide,

Wide world peering into human dwellings

O, moon, stand still for a moment,

Tell me, ah, tell me where is my lover!

Tell him. please, silvery moon in the sky,

That I am hugging him firmly,

That he should for at least a while

Remember his dreams!\

Here, Jana Valashkova is singing with the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra. It’s a song that’s very much about loneliness and longing.

Let’s go back to Mahler and hear a by him song called The Lonely One in Autumn.

Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, The Song of the Earth, is an extraordinary work, a composition for two voices and orchestra that was described as a symphony when it was published in 1909.

Mahler composed this work following the most painful period in his life, and its six songs address themes such as those of living, parting and salvation. Three disasters befell him in the summer of 1907. Political manoeuvering and anti-semitism forced him to resign as director of the Vienna Court Opera, his daughter Maria died from scarlet fever and diphtheria, and Mahler himself was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect.

"With one stroke," he wrote to his friend Bruno Walter, "I have lost everything I have gained in terms of who I thought I was, and have to learn my first steps again like a newborn".

The year 1907 also saw the publication of a German translation of the Chinese Flute, a volume of ancient Chinese poetry that absolutely captivated Mahler. And so he chose some of the poems to set to music as Das Lied von der Erde.

Autumn fog creeps bluishly over the lake.

Every blade of grass stands frosted.

As though an artist had jade-dust

over the fine flowers strewn.\

The sweet fragrance of flower has passed;

A cold wind bows their stems low.

Soon will the wilted, golden petals

of lotus flowers upon the water float.\

My heart is tired. My little lamp

expired with a crackle, minding me to sleep.

I come to you, trusted resting place.

Yes, give me rest, I have need of refreshment!\

I weep often in my loneliness.

Autumn in my heart lingers too long.

Sun of love, will you no longer shine

Gently to dry up my bitter tears?\

This, then, is The Lonely One in Autumn, with the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Otto Klemperer. I am sorry but I do not know who the singer is.

I would like to do something a bit unusual before we finish. The first piece you heard this morning was commonly known as Marietta’s Song, from Korngold’s The Dead City. Let’s hear that piece again, but this time a heart-breaking transcription for violin played by Nicola Benedetti. She’s playing with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra.

Featured composers:

Featured genres:

Loneliness and Longing playlist

Each Spotify track has been chosen specifically; however, the corresponding YouTube videos may be performed by different orchestras.